David Lamelas, Quand le ciel bas et lourd – public campaign

In early December 2020 the gallery launched a public campaign to save a major public work by David Lamelas, Quand le ciel bas et lourd (1992) situated in the park of the Royal Museum of Fine Arts in Antwerp. Due to a mistake in the planning of a new entrance for the museum that is currently under renovation, it had become unavoidable to move the work. Last summer the Flemish authorities regrettably withdrew their initial support to rebuild the piece on the same site and the existence of the work is now seriously threatened.

A first letter by Lamelas from September 2020 sent to Jan Jambon, Flemish minister of Culture, asking him to revert his decision remained unanswered. Therefor the gallery decided to launch a campaign asking people to co-sign the artist’s letter. By the time the letter was resent to the minister (December 16) 840 artists, curators, museum directors, critics, gallerists and art lovers from Belgium and all over the world had signed it.

Please scroll down for the letter to Jan Jambon, the list of co-signatories, the reactions from Bart De Baere, director of the M HKA who owns the piece, the reaction of the gallery and artist to De Baere’s response as well as a growing list of press articles and general information on the work.

If you wish to show your support we still invite you to sign and your name will be added to the list. We will continue to update this part of our website with any new developments.

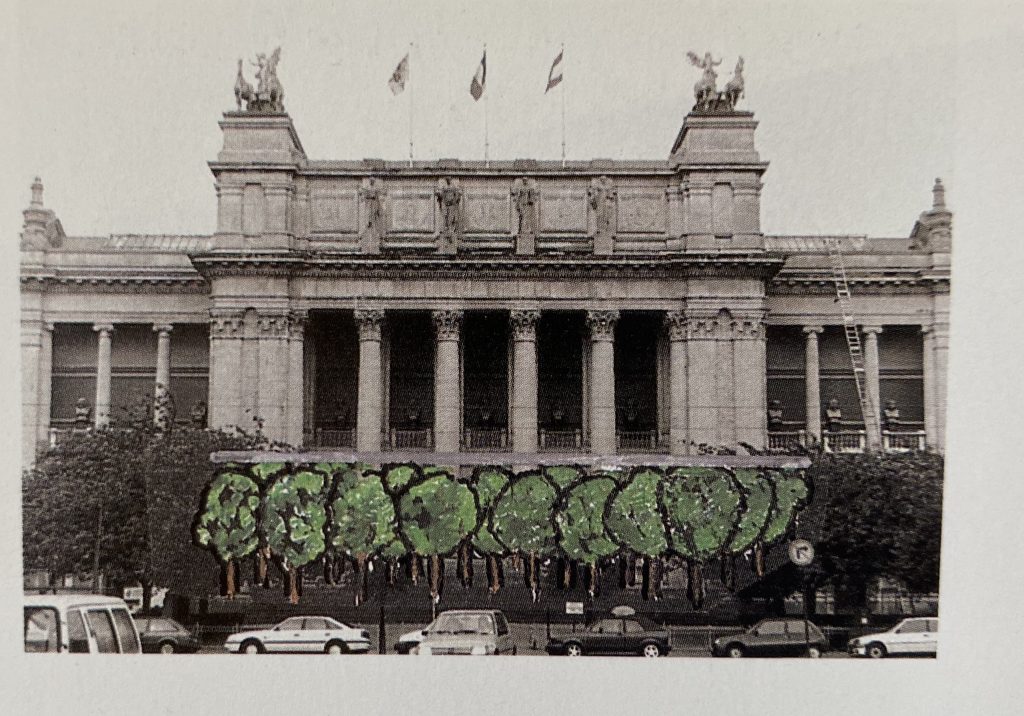

David Lamelas, Quand le ciel bas et lourd (When the sky low and heavy), 1992, view at the Royal Museum of Fine Arts (KMSKA) in Antwerp, 2021, photograph by Nattida-Jayne Kanyachalao. In the collection of M HKA, Antwerp, donation by the artist in 2011.

Realised on the occasion of the exhibition ‘America, Bride of the Sun: 500 Years Latin-America and the Low Countries’, held at KMSKA in 1992 and curated by Catherine de Zegher and Paul Vandenbroeck, production: Kunststichting Kanaal, Kortrijk.

Letter from David Lamelas to Jan Jambon (17/09/2020)

Cc: Bart De Baere, director MUHKA; Carmen Willems, director KMSK; Bart De Wever, mayor of the city of Antwerp; Marina Laureys, Department of Culture; Jan Mot, gallerist of David Lamelas in Brussels.

Buenos Aires, September 17, 2020

Dear Mr Jambon,

I was very surprised and disappointed to learn about your decision to dismantle my work Wanneer de lage, zware lucht on the site of the KMSK in Antwerp. With this letter I wish to express that I oppose this decision. In 2011 I donated this work to the MUHKA stipulating my desire to keep it on the site and hoping it would be safeguarded by a trustworthy public collection at its current location.

My work was produced on the occasion of the exhibition ‘America. Bride of the Sun: 500 Years Latin-America and the Low Countries’ held at the KMSK in 1992. Meanwhile, the sculpture has become part of the urban and artistic history of the City of Antwerp. Moreover, it is one of the very rare monuments in all of Belgium with a clear anti-colonial content and therefore it is a very actual work. During the current times of growing awareness, it would be very disturbing to erase it from the landscape of a country with a heavy colonial past. The work is described in a document of the MUHKA as containing multiple metaphorical layers: between nature and industrial structures, as well as a second layer of oppression that came forth from the topic of the above mentioned exhibition, namely the past conquista of South America. But it also refers to the colonial past of Belgium where the exploitation, suppression and terror in Congo resulted in the bourgeois grandeur that is strikingly apparent in the building of the museum (KMSK) itself and its surrounding residences.

In addition the MUHKA text states: The position that David Lamelas chose on the premises of the museum refers to the importance of the international post-war avant-garde that was present in Antwerp in the two places of contemporary art from the 1960s, Wide White Space and A 37 90 89 near the museum, and as a sculpture it keeps the memory of these places alive and guarantees critical reflection on institutions and the bourgeois base of art.

During one of the earlier meetings with Bart De Baere as well as with several people from the Department of Culture, I agreed with the option to rebuild the piece some 25 meters towards the building where my former gallery, Wide White Space, was located. This proposal still seems like a very good idea to me and I hope we can move forward with this plan.

I wish to thank you for your consideration and look forward to your reaction.

David Lamelas

List of co-signatories

| Philippe Van Cauteren | Sven Augustijnen | Antony Hudek | |

| Luc Tuymans | Elena Filipovic | Morris Vandaele | |

| Annie Gentils | Anny De Decker | Pablo León de la Barra | |

| Luk Lambrecht | Jan Mot | Tinne Bral | |

| Elias Cafmeyer | Stella Lohaus | Andrew Hunt | |

| Kati Heck | Julia Wielgus | Ami Barak | |

| Tom Van Camp | Caroline Dumalin | Maud Vervenne | |

| Manon de Boer | Nico Dockx | Laura Hanssens | |

| Koen Theys | Catherine de Zegher | Haro Cumbusyan | |

| Winnie Claessens | Fari Shams | Bruno van Lierde | |

| Leen De Brabandere | Jelle Breynaert | Steven Tallon | |

| Devrim Bayar | Marc Ruyters | Peter Handschin | |

| Abdalla Al Omari | Guy Van Bossche | Bert de Leenheer | |

| Catherine David | Johan Pas | Zoë Denys | |

| Laura Herman | Pierre Bismuth | Iris Paschalidis | |

| Elke Segers | Dimitri Riemis | Moritz Küng | |

| Katrien Loret | Antonius Theelen | Jacques Heinrich Toussaint | |

| Nina Hendrickx | Tim Van Laere | Peter Galliaert | |

| Olivier Pacquée | Mekhitar Garabedian | Corinna Kirsch | |

| Jesse Van Bauwel | Sophie Nys | Richard Massey | |

| Kasper Bosmans | Eva Wittocx | Sieglinde Woerndle | |

| Hidde van Schie | Nav Haq | Mladen Bizumic | |

| Emilie Legrand | Adam Szymczyk | Emmy Tawil | |

| Cis Bierinckx | Christine Lambrechts | Jochen Meyer | |

| Karin Hanssens | Bram Bots | Mercedes Cohen | |

| Guillaume Bijl | Ann Debeuf | Hilde Pauwels | |

| Martin Hatebur | Pedro de Llano Neira | Shanglie Zou | |

| Philip Van den Bossche | William Vanhassel | Alain Servais | |

| Véronique Vaes | Martine Depestel | Marie-Pascale Gildemyn | |

| Joëlle Tuerlinckx | Christoph Fink | Hilde Van Gelder | |

| Mia Van Hool Vuylsteke | Christine Binswanger | Tom Engels | |

| Aline Van Nereaux | Tim Theo Deceuninck | Kathleen Weyts | |

| Joost Elschot | Emma Van Geet | Dialogist Kantor | |

| Nannick De Coster | Anne-Claire Schmitz | Alex Reynolds | |

| Jeroen Staes | Nanny Schrijvers | Eduardo Rivero | |

| Thibaut Verhoeven | Geert Wijns | Charlie Voet | |

| Ben Sledsens | Harald Thys | Anne Pontegnie | |

| Elea De Winter | Natalie Gielen | Sven Boel | |

| Sammy Baloji | Georges Staes | Geert Vanthournout | |

| Aaron Harris | Anne-Mie Van Kerckhoven | Sebastiaan Peeters | |

| Oriol Vilanova | Jan Kempenaers | Paul Geelen | |

| Freddie Checketts | Stefano Cernuschi | Andrea Galiazzo | |

| Sofie Van de Velde | Ann Hoste | Umer Butt | |

| Michal Wolinski | Aram Moshayedi | Koenraad Dedobbeleer | |

| André Duijsters | Fabian Flückiger | Mariska De Mey | |

| Ria Pacquee | Robert Milne | Natacha Mottart | |

| Solange de Boer | Ann-Shelton Aaron | Christine König | |

| Isabella Ritter | Charles Gohy | F M Uitti | |

| Guilia Bellinetti | Giovanni Carmine | Johan Vansteenkiste | |

| Etienne Wynants | Pablo Florez | Liesbet Waegemans | |

| Sabine Breitwieser | Carla Acevedo-Yates | Nikolaus Tacke | |

| Prateek Raja | Jacob King | Christine Clinckx | |

| Pol Le Vaillant | Yves Mettler | François Curlet | |

| Wilfried Huet | Vincent Clay | Bart Cassiman | |

| Bas Geenen | Wendelien van Oldenborgh | Orhan Ayyuce | |

| Alfred Vandaele | Barbara von Fluë | Rebecca Harris | |

| Pilar Roca | Marie Muracciole | Tinka Pittoors | |

| R Nota | Martine Laquiere | Chantal Crousel | |

| Heidi Voet | Michel Assenmaker | Lucinda Cowell | |

| Luc Haenen | Bart Staes | Krien Mohr | |

| Francis Carpentier | Eric de Bruyn | Kaori Shiota | |

| Paul Carpentier | Heidi Ballet | Eric Rinckhout | |

| Griet Lebeer | Maria Inés Rodriguez | Alejandro Cesarco | |

| Martine Van den Broeck | Tamara Beheydt | Jozefien Van Beek | |

| Kimberly Hoskens | Carrie Pilto | Jurgen Marchand | |

| Daniëlla Van Remoortere | Claude Lorent | Bart Macken | |

| Andreas Gegner | Clément Delépine | Lorenzo Giusti | |

| Sharon Lockhart | Julie Pfleiderer | Elizabeth Calzado | |

| Olivier Bellflamme | Roger D'Hondt | Lieva Claeys | |

| Marion De Cannière | Filip Van Dingenen | Vasilis Zarifopoulos | |

| Inge Grognard | Ronald Michaelson | Hilde Wellens | |

| Pieter Geerts | Nick Geboers | Maximilian Hagemes | |

| Win Van den Abbeele | Philipp Fernandes do Brito | Cindy Lorraine | |

| Helga Duchamps | Pascale Viscardy | Das Christiaan | |

| Sofie Haesaerts | Mathieu Zurstrassen | Elise Rasmussen | |

| Tom Peeters | Eliana Blechman | Agustin Perez Rubio | |

| Louis-Philippe Van Eeckhoutte | Caro Vanderbeck | Jo Op de Beeck | |

| Katrien Reist | Margaret Honda | Leen Van Backlé | |

| G. T. Pellizzi | André Rottmann | Ilse Luyten | |

| Gert Adriaenssens | Dessislava Dimova | Gerry Smith | |

| Nan van Houte | Marc Senden | Valerie Verhack | |

| Ekaterina Vorontsova | Elsa Koenig | Ory Dessau | |

| Sacha Aerts | Nano Orte | Melanie Deboutte | |

| Kathy Solomon | Jan De Meester | Magnolia De la Garza Molina y Vedia | |

| Simon Delobel | David Horvitz | Lidwine Vander Heyde | |

| Frank Maes | Margarita Maximova | Angela Bartholomew | |

| Vera Van Hecke | Eva Peleman | Pieter Vermeulen | |

| Maxime Van Melkebeke | Els van Riel | Narcisse Tordoir | |

| Johanna Cypis | Anne Pöhlmann | Ariel Aisiks | |

| Tommy Simoens | Bert Van Welden | ferranElOtro | |

| Lilou Vidal | Lander Savelkoul | Elias Leytens | |

| Pieter Vermeersch | David Claerbout | Koen Van Synghel | |

| Pol Matthé | Jan Van Imschoot | Nele Samson | |

| Juan Pablo Plazas | Annina Zimmermann | Koen Vaessen | |

| Kirsten Horemans | YU Xiaoying | Luk Sips | |

| Mira Verheyden | Joeri Mahieu | Wesley Meuris | |

| Annebel Courtens | Michel Moortgat | Barbara de Jong | |

| Edith Doove | Voebe De Gruyter | Bert Danckaert | |

| Xavier Garcia Bardon | Stefan Dhaenens | Kristof Berckmans | |

| Katrien Van Hecke | Stefan Benchoam | Astrid Loos | |

| Nicholas Van Noten | Joris Hulstaert | Barbara Vermoortele | |

| Stijn Buyst | Leen Duffeler | Jean Pierre Ferré | |

| An Goovaerts | Daan Rau | Saar De Buysere | |

| An Vanderveken | Andrea Lissoni | Frederik Lizen | |

| Bram van meervelde | Raymond Liekens | Kristof Delie | |

| Johannes van der Klaauw | Victoria Giraudo | Sven 't Jolle | |

| Katy Crowe | Oscar Rommens | Kurt Marx | |

| Dominik ' t Jolle | Simon Moretti | Peter Bernaerts | |

| Ilse Aerts | Nora Mecibah | Joyce Meuleman | |

| Mieke Mels | Jan Glorieux | Cindy Roelant-Blom | |

| Maria Blondeel | Tom Cools | Mathilde Warusfel | |

| Bie Hooft-De Smul | An De Bruyne | Esther Bleyenberg | |

| Paul L. Van Haegenbergh | Johan Vandermaelen | Claudia Soccio | |

| De Wilde Sarah | Minneke Mecibah | Paul Gees | |

| Maria Kley | Paul Van Hoorick | Arlette Bert | |

| Inge Salden | Hans Van Grinderbeek | Robin Angst | |

| Piet Coessens | Nej De Doncker | Veronique Van Turnhout | |

| Rein Vyncke | Pascale Wils | Pierre Lhoas | |

|

Bojana Cvejic

|

Axel Daeseleire | Julie Carlier | |

| Raffaella Cortese | Nel Aerts | Marijke Dekeukeleire | |

| Anne Daems | Anais Lambert | Michiel Vandevelde | |

| Serge Henkens | Christine Gerits | Frank Benijts | |

| François Speleman | Anke van Altena | Axelle Manguila Husikama | |

| Nuran Karaca | Pieter Verbeke | Johan Debruyne | |

| Michael Raedecker | Chris Roodhooft-Cnop | Marc de Blieck | |

| Laurens Germanes | Tim Broos | Peter De Graef | |

| Jimmy Janssens | Suchan Kinoshita | Dylan Delval | |

| Lina Ejdaa | Siska Bulkens | Rebecca Beers | |

| Bram Vandeveire | Sam Cristael | Tom Flamant | |

| Pascale Engelen | Carlos Navarrete | Odette Raassens | |

| Béatrice Balcou | Kaat De Schepper | Barbara und Axel Haubrok | |

| Douglas Park | Caroline Dossche | Chantal De Smet | |

| Luc Van Laer | Johannes Muselaers | Rik Vanmolkot | |

| Louise Wauters | Louis Hulstaert | Andy Vandevyvere | |

| Sebastiaan Maes | Stijn De Munck | Femke Cools | |

| Stefan de Clippele | Wim Catrysse | Annick De Gres | |

| Yuki Okumura | Ann Van Aken | Vedran Kopljar | |

| Linda Van Tulden | Kristine Castro | Stéphane Le Mercier | |

| Wim De Pauw | Nathalie Verlinden | Maria Pagkos | |

| Maïté Vissault | Katie Lagast | An Willems | |

| Jan Pillaert | Ann Van Loon | Johan De Greef | |

| Patricia Martin | Chris Beuckels | Simona Denicolai & Ivo Provoost | |

| Pierre Huyghebaert | Paul Domela | Rein De Wilde | |

| Ulrike Lindmayr | Wilfried Cooreman | Maureen Cordens | |

| Leen Lampo | Tristan Gielen | Thierry Mortier | |

| Elisa Nuyten | Axelle Stiefel | Eline Ledent | |

| Elisabeth Hapers | Carina Verschueren | Filiep Libeert | |

| Aglaia Konrad | Egbert Aerts | Rita Geerts | |

| Yamina El Atlassi | Moriah Mudd-Kelly | Annick Liekens | |

| David Evrard | Jan Vandenhoeck | Muriel Geryl-Simon | |

| Jill Bertels | Christophe Coppens | Perry Roberts | |

| Isabelle de Visscher-Lemaitre | Sara Bomans | Rien Schellemans | |

| Birgit Lesage | Nicole Van Loon | Els Ceulemans | |

| Olivier De Jonghe | Kristin Van der Weken | Ann Coenen | |

| Emmanuelle Quertain | Stijn Ank | Jo De Clercq | |

| Laurent Dupont | Pit De Jonge | Eglantine Möller | |

| Eric Bracke | Lotte Van den Audenaeren | Jeroen Laureyns | |

| Michel Maurice Will | Jef Vrelust | Sara De Roo | |

| Nina-Joy Thielemans | Vincent de Roder | Eve Bouyer | |

| Bart Baele | Bart Beys | Muriel Dewimille | |

| Annemie Maes | Inke Coolen | Stijn Yperman | |

| Nicoline van Stapele | Maximilian Wichary | Philippe A.Y. Seynaeve | |

| Sigrid Batens | Francois Sage | Sander De Groote | |

| Vanhecke Lut | Bart Bomans | Bram Malisse | |

| Susanne Weck | Lieven Van Den Abeele | Arpaïs Du Bois | |

| Pierre Leguillon | Brigitte Spiering | Oscar Tuazon | |

| Ana Castella | Kris Baetens | François Piron | |

| Lieve Van Cleemput | Patsi Maes | Raymond Pask | |

| Markéta Skarban | Yves Gevaert | Hilde Van Essche | |

| Ingrid Deuss | Carla Sleutel | Nadine Van De Schoor | |

| Jef Huybrechts | Florence Cheval | Jeannine Luyten | |

| Soens Elisabeth | David Maroto | François Breugelmans | |

| Filip Verreyke | Ines Tyberghein | Joannes Késenne | |

| Els Van Droogenbroeck | Mulugeta Tafesse | Olivier Van Dessel | |

| Bambi Ceuppens | Anita Verheecke | Tine De Meulder | |

| Henk Delabie | Marc Tops | Mirco Bimbi | |

| Joke Zuidgeest | Johnny De Meester | Jan Schaeken | |

| Olaf Coart | Marcel Smarius | Bodo Peeters | |

| Paul Wauters | Isabel Broeckx | Rudi Angst | |

| Daniël Dewaele | Mirko Vonck | Theun Vonckx | |

| Tom Meskens | Thijs Paijmans | Peter De Boeck | |

| Hannah De Corte | Jolien Siaens | Babette Cooijmans | |

| Truus Aelbers | Eva Peters | Marc Wauters | |

| Ans Aerts | Barbara Van den Eynde | Jonas Lohaus | |

| Ester Torres Falcato Simões | Ann Van Halewyck | Pippe Steenhoudt | |

| Rinus Van de Velde | Maartje Fliervoet | Heidi Vanhaverbeke | |

| Franz Van den Brande | Ria Thys | Valentijn Peeters | |

| Natasha Casteleyn | Riet Van der Plas | Katrien Bruyneel | |

| Niki Vissers | Ann Van den Bempt | Evita Willems | |

| Veerle Michiels | Verbeurgt Leen | Sabine Vanderplasschen | |

| Lisette Geuens | Bénédicte Deliens | Philippe Braem | |

| Peter Morrens | Sarah Lavrysen | Judith Fierens | |

| Delphine Dubourg | Liliane Dewachter | Danijela Susko | |

| Winke Besard | Gabriel Palumbo | Jill Drossaert | |

| Maude Michils | Tessa van Thielen | Jasmien Talloen | |

| Daniel Steegmann Mangrané | Stephanie Duval | Fien Ariën | |

| Lena Duchateau | Linda Suy | Melanie Meyskens | |

| Coene Koert | Quinten Clause | Thys Frieda | |

| Ana Miguel | Valerie Stevens | Dominique Froyen | |

| Joost Surmont | Wouter Tousseyn | Eva De Jaegere | |

| Lauren Vander Cruysse | Ellen Laumans | Ilse Raps | |

| Stefan Kraus | Ingrid Rooms Khan | Kim Priels | |

| Jochem Vanden Ecker | Matt Hinkley | Sarah Wéry | |

| Laura Greffe | Zoë Gray | Astrid Holsters | |

| Béatrice Josse | Jeanette Pacher | Florian Kiniques | |

| Georges Uittenhout | Fanny Gonella | Veerle Herbosch | |

| David Helbich | Christophe Clarijs | Maj Verheijen | |

| Kasper König | Thomas Bernardet | Andreas Prinzing | |

| Ann Veronica Janssens | Malgorzata Ludwisiak | Maartje Claes | |

| Luc Van Santvoort | Nicolas Lelièvre | Sixtine Bérard | |

| Shervin Sheikh Rezaei | Robin Schaeverbeke | Laurens Otto | |

| Lena Mariën | Els Bouden | Rozemarijn De Keyser | |

| Luna Vanhaecke | Ellen Baert | Beatrice Pecceu | |

| Daan Gysels | Thierry Vandenbussche | Jet de Kort | |

| Annelies Nagels | Claudine Hellweg | Adam Van Den Berghe | |

| Tanja Boon | Liesbet Grupping | Martina Lattuca | |

| Jorik De Wilde | Louise Souvagie | Chasseur Phillippe | |

| Doug Henry | Rebecca Jane Arthur | Nick Oberthaler | |

| Marjan Verhaeghe | Chloë Delanghe | Pedro Ramos | |

| Tina Schulz | Michael Vervroegen | Vincent Vulsma | |

| Martijn van Nieuwenhuyzen | Stefan Hommerin | Denis Gielen | |

| Maarten Desmet | Marie Logie | Lies Ghyoot | |

| Peter Coen | Danny Boone | Michèle Homburg | |

| Job Guillaume | Lien Wauters | Alexis Blake | |

| Jos de Gruyter | Kristoffer Raasted | Rineke Dijkstra | |

| Samuel Saelemakers | Maxime Martens | Vanessa Desclaux | |

| Helena Kritis | Paul Kuimet | Bram Van Damme | |

| Bart Richart | Yiannis Papadopoulos | Tine Wilberts | |

| Ane Mette Hol | Gert Renders | Suse Weber | |

| Adrien Tirtiaux | Paul Hendrikse | Frederik Vergaert | |

| Ralph Collier | Ilse liekens | Pamela Echeverría | |

| Zanna Gilbert | Michel Kengen | Hendrik Van Walleghem | |

| Jan Hendrickx | Els Hubert | Fee Veraghtert | |

| Jan Vindevogel | Francis Alÿs | Christophe Gallois | |

| Jelle Desmet | Ine Engels | Boris Steiner | |

| Stephanie Kiwitt | Aleksandra Chaushova | Els Vermang | |

| Frans Vercoutere | Annie De Winne | Carlo Vansant | |

| Vincent Meessen | Veerle Meul | Gert Audenaert | |

| Emilie Lecouturier | Sara Ceroni | Marco Filippa | |

| Wim Van der Velden | Philomene Magers | Lise Duclaux | |

| Nadim Vardag | Greet Stappaerts | Sabine Herrygers | |

| Hélène Guenin | Kaat Vannieuwenhuyse | Lieve Schoeters | |

| Maria C.M.P de Pontes | Birgit Van de Leest | Estelle Labes | |

| Gui Polspoel | Carlos León-Xjimenez | Carine Van Dyck | |

| Barbara van Ginneken | Angel Sarmiento | Guillermo Romero Parra | |

| Ula Sickle | Ilse Leemans | Sol García Galland | |

| Yasmil Raymond | Mary Szydlowska | Lu-Ann Tsai | |

| Selin Eskin | Simon Saerens | Amber Vanluffelen | |

| Dirk Kenis | Sarah van Lamsweerde | Mette Edvardsen | |

| Agnieszka Bolek | Barbara Pereyra | Karel Burssens | |

| Siska Claessens | Kevin Gallagher | Evelien Cammaert | |

| Jaro Straub | Vergara Angel | Sabrina Seifried | |

| Justyna Gajko Berckmans | Els Silvrants-Barclay | Jan(us) Boudewijns | |

| Marie-Renée van Beurden | Hilde Debuck | Maud Gyssels | |

| Bartomeu Marí | Freek Wambacq | Nelly Voorhuis | |

|

Jan Van Broeckhoven |

Kato Van Roey | Tina Isabella Hild | |

| Barbara De Coninck | Caroline Vermeulen | Jan Schrenk | |

| Johan Smets | Tine De Ruysser | Tris Vonna-Michell | |

| Veronika Pot | Macha Roesink | Clara Gevaert | |

| Anne-Marie Poels | Victor De Vocht | Clare Noonan | |

| Jan Vercauteren | Patricia De Laet | Damien Noël | |

| Christa Iwu | Harper Montgomery | Etienne Courtois | |

| Ann Puttemans | Servaas Verbergt | Kitty Bons | |

| Giuditta Zaniboni | Philippe Pirotte | Kasper De Vos | |

| Rik Maeck | Charlotte Dossche | Sarah Watson | |

| Mario Barrantes Espinoza | Constance Neuenschwander | Re'al Christian | |

| Carla Arocha |

Hannah Van Remoortere

|

Alice De Mont | |

| Johan De Decker | Femke Gyselinck | Joanna Mytkowska | |

| Dimitri Vangrunderbeek | Ronny Heiremans | Katleen Vermeir | |

| Mieke Teirlinck | Katrien Roos | Johan Vandeghinste | |

| Wim Van Mulders | Sofia Jones | Veva Roesems | |

| Barrio Charmelo Amanda | Jeroen Dossche | Federico Vladimir Strate | |

| Max Colombie | Cyriaque Villemaux | Faye Holdert | |

| Belinda Hak | Stijn Kemper | Rik Desaver | |

| Jonas Devos | Suzy Castermans | Wouter Davidts | |

| Camille Bladt | Annelies Vaneycken | Stefaan Vervoort | |

| Ben Pointeker | Dimitri Reist | El hadj Libasse KA | |

| Franky D.C | Emmanuela Buonsenso | Judith Verhoeven | |

| Marleen Peeraer | Yana Van Ginneken | Lisa Panting | |

| Manon van den Eeden | Joeri Arts | Sabine De Bock | |

| Eline Vandewiele | Pierre Bal-Blanc | Daniel Baumann | |

| Pieter Van Reybrouck | Eric Angelini | Tristan Ledoux | |

| Nicolas Florence | Ludo Janssens | Annemie Ghekiere | |

| Anja Isabel Schneider | Cécile Angelini | Veerle Calcoen | |

| Veerle Calcoen | Bram Calcoen | Oliver Lenaerts | |

| Herman van den Boom | Bart Roefmans | Céline Djermag | |

| Johan Witdouck | Kim Rothuys | Sonia Niwemahoro | |

| Jesus Fuenmayor | Catherine Mayeur | Vijai Maia Patchineelam | |

| Lieve Van Coillie | Ine Vlassaks | Joy Sleeman | |

| Willem Asselbergs | Puck Rouvroye | Chris Eneman | |

| Maarten Vanhee | Marianne Sneijers | Ruth Coremans | |

| Jules Bouwen | Anne Bambynek | Marie Zolamian | |

| Nathalie Eeckman | Marc Rossignol | Nikolaus Gramm | |

| Anne-Sophie Fontenelle | Tony Jacobs | Nadia Vilenne | |

| Michel Feyen | Ricardo Valentim | Olivier Foulon | |

| Elize Mazadiego | Javier Villanueva | Chris McCormack | |

| Viviane Klagsbrun | Claire Burrus | Simon Patterson | |

| Patricia Bickers | Dimitri Hemelsoet | Francesca Valentini | |

| Kristina Newhouse |

List updated on 14/05

Open letter from Bart De Baere (11/12/2020)

Dear David, Dear Jan, and everyone who signed the letter to the Minister-President,

We are pleased to see the support that has been expressed, and the momentum that has grown over the past few days around Quand le ciel bas et lourd, the work by artist David Lamelas, which has defined the public space alongside the KMSKA on the corner of Schildersstraat and Plaatsnijdersstraat since 1992. It is thrilling to count more than 700 signatures, including many names that carry a lot of weight for us, all within a week’s time on a letter advocating the preservation of an exemplary work of art. Such a positive dynamic gives us the courage to invest further energy into this matter. We are grateful to each and every one of you.

For almost two years now, discussions have been underway with various key players about the possible relocation of this work, which cannot be retained at its current location due to the large-scale renovation of the KMSKA. The many discussions have also led to a murky situation in some areas. The current impetus and the opening lines of the letter of support remind us that it is important in this case to clarify the situation with everyone. In this letter we want to paint a nuanced picture that can form the basis for jointly ensuring a concrete and positive follow-up for the work. A brief summary of the facts:

Quand le ciel bas et lourd by David Lamelas was installed in 1992 in the garden of KMSKA for the exhibition “America Bride of the Sun”. It has a site-specific dimension; it interrogates the bourgeois architecture surrounding it from a post-colonial perspective, and also bridges the avant-garde history of the neighbourhood with the artist’s former gallery, Wide White Space, which was at one time located in the art nouveau house on the corner across from the museum.

In 2011, the work was donated to M HKA by the artist after the museum contacted him as part of its historiographic project. M HKA has since made the work a key reference in its collection.

In 2018, the approach to the surrounding park around KMSKA was put on the agenda as a next phase of the overall plans to refurbish the museum premises. M HKA heard that there seemed to be a problem with the work in the new plans, and enquired about this with the Flemish culture administration on 24 June 2018. The work of art turned out to be located in the way of the new supply route of the security services and of the museum’s new freight lift. Calculation of the turning circles for the trucks failed to provide an alternative solution.

The memorandum on Quand le ciel bas et lourd that M HKA attached to its question to the administration not only defended the importance of the work but also mentioned two possible solutions in case the problem could not be resolved:

– relocation of the work in the park, closer to Wide White Space, subject to the artist’s agreement.

– purchase of another work by David Lamelas as compensation.

The artist did not choose the second option, but was in favour of the first proposal for a relocation closer to the former Wide White Space gallery.

The designers from Team van Meer, who were responsible for the garden redesign, created a new design at the request of the steering group for the KMSKA masterplan. The artist agreed with this proposal.

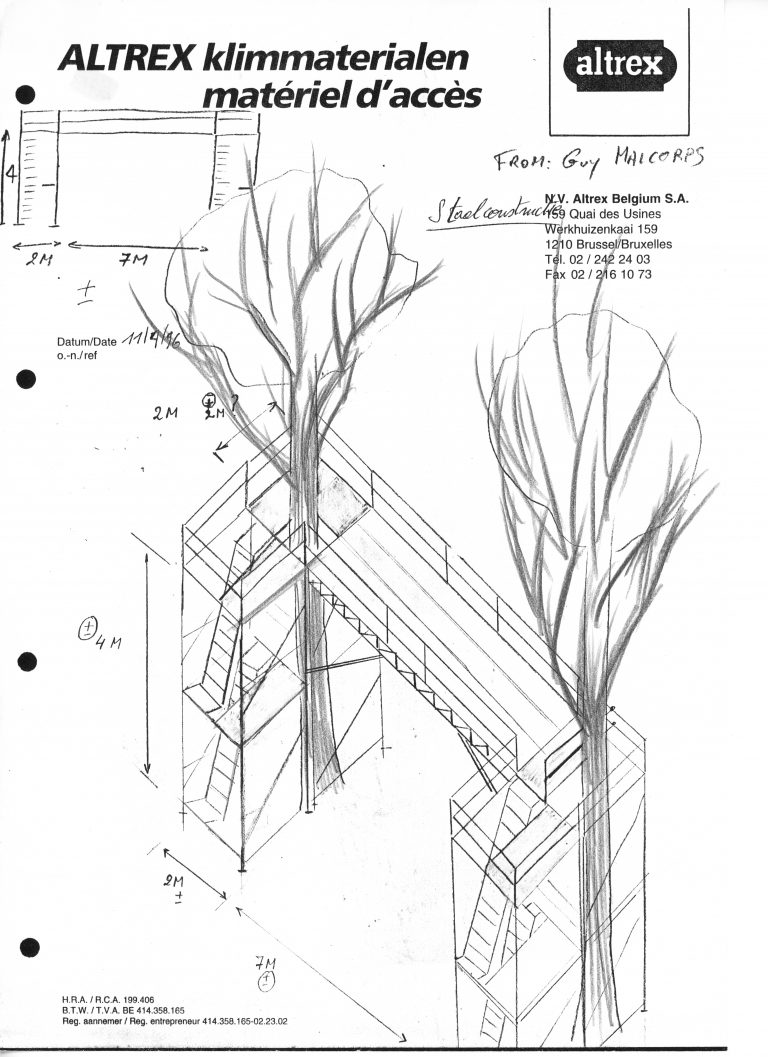

Team van Meer estimated that the rebuilding of the steel structure would cost 110,000 euros. During the permit process, Flanders Heritage Agency Onroerend Erfgoed issued a negative opinion on the proposal of a relocation and various city services apparently did so as well during the design process.

In the spring of 2020, Minister-President Jan Jambon decided not to go ahead with the proposal for a new edition of the work on the basis of these facts.

M HKA understood this decision: there was no budget space within the envelope allocated to KMSKA and the time frame for reopening KMSKA was tight.

At that time, the city government was thinking in terms of a relocation of the work to the Middelheim Museum, disregarding its site-specific dimension.

In June 2020, M HKA was in contact with the artist and examined alternative locations elsewhere in the South district of Antwerp. The artist felt that this was not appropriate. M HKA consulted various actors within the city to see if any initiative on that side was possible in the short term.

On August 28, 2020, the council of aldermen of the City of Antwerp validated the final design of the garden presented to them by the Flemish administration, which did not include a new edition of the artwork. This provided a basis for the following steps in the redevelopment of the park: permits, agreements on periodic maintenance of green areas, public tenders. The start of the redevelopment of the park was scheduled for February 2021.

On September 18, 2020, the artist sent an email to the Minister-President in which he expressed the wish that the work be preserved on the site.

On September 21, 2020, M HKA had a – previously planned but postponed – appointment with the Minister-President’s office. In a new memorandum, M HKA presented arguments to the Minister-President for the desirability of nevertheless relocating the work and offered to undertake its production. The Minister-President accepted this, but explicitly asked for the agreement of KMSKA.M HKA immediately received a positive response from KMSKA, both from the chairman of its Board of Directors and from its director, as well as from the KMSKA masterplan steering group. The planned works on the garden were of course not stopped. It was decided that the necessary dismantling of the current edition of the artwork would be documented in consultation with M HKA, with an eye to the production of the new edition.

November 2020: M HKA started preparations for the production.

It will have to face several challenges at the same time: supervising the dismantling of the work, working out the concrete aspects of the relocation itself, finding the financial means and obtaining the necessary permits from the city. In addition to these practical steps, M HKA also wishes to work substantively by planning a presentation and various events that will further situate the artwork within an art historical perspective, but also in the context of renewed societal support for the work.

Writing to the Minister-President is therefore no longer relevant in this regard. The responsibility for the work Quand le ciel bas et lourd is currently, and unambiguously, in the hands of M HKA, which had previously shown commitment to the artwork and expressed the desire to take up its cause. M HKA is not alone in this, and is also now bolstered by the broad support that the petition letter demonstrates.

In any case, the work will be dismantled in February, and if it is up to us, it will be relocated in the same area in the foreseeable future.

We agree with you that this is an exceptional work and a key work in various ways. We will keep you informed on this exciting story and we will be happy to involve you as much as possible.

Sincerely,

Bart De Baere, Director

(source: https://blog.muhka.be/en/dear-david-dear-jan-and-everyone-who-signed-the-letter-to-the-minister-president/)

Geachte David, geachte Jan, geachte ondertekenaars van de brief aan de minister- president,

We zijn blij met de steun en dynamiek die de laatste dagen werd uitgedrukt rond het werk ‘Quand le ciel bas et lourd’ van kunstenaar David Lamelas dat sinds 1992 de publieke ruimte langs KMSKA op de hoek van de Schildersstraat en de Plaatsnijdersstraat markeert. Het is aangrijpend om binnen de termijn van een week meer dan zevenhonderd ondertekenaars te tellen bij een brief die het behoud van een kunstwerk bepleit, met daaronder vele namen die voor ons van groot gewicht zijn. Dit geeft ons de moed om verder energie in dit dossier te investeren. We zijn elk van u dankbaar.

Sinds bijna twee jaar wordt er met verschillende protagonisten overlegd rond de mogelijke herplaatsing van dit werk dat omwille van de grootscheepse renovatie van het KMSKA niet op de huidige locatie behouden kan blijven. De vele discussies hebben ook enkele schaduwzones veroorzaakt. De huidige dynamiek en de aanhef van de steunbrief herinneren ons eraan dat het belangrijk is om de situatie in dit dossier helder met iedereen te delen. In deze brief willen we een genuanceerd beeld schetsen dat een basis kan vormen om samen een concreet en positief vervolg te garanderen voor het werk. Een kort feitenoverzicht:

- Quand le ciel bas et lourd van David Lamelas werd in 1992 in de tuin van KMSKA gerealiseerd voor de tentoonstelling ‘Amerika Bruid van de Zon’. Het heeft een site-specifieke dimensie; het gaat vanuit een postkoloniale vraagstelling in op de bourgeois architectuur eromheen, en slaat ook een brug naar de avant-garde voorgeschiedenis van de buurt met de voormalige galerij van de kunstenaar, Wide White Space, ooit gevestigd in het art- nouveauhoekhuis er tegenover.

-

In 2011 werd het werk aan M HKA geschonken nadat het museum de kunstenaar contacteerde in het kader van zijn historiografisch project. M HKA valideerde het werk sindsdien als kernreferentie in de collectie.

-

In 2018 kwam de aanpak van het omliggende park rond KMSKA op de agenda. M HKA hoorde dat er een probleem met het werk zou zijn en informeerde hiernaar bij de administratie cultuur op 24 juni 2018. Het kunstwerk bleek in de aanvoerroute te staan van de veiligheidsdiensten en van de nieuwe goederenlift van het museum. Berekeningen van draaicirkels van vrachtwagens leverden geen alternatieve oplossing.

-

De nota over Quand le ciel bas et lourd die M HKA toen bij zijn vraag voegde, argumenteerde niet enkel het belang van het werk maar vermeldde ook twee mogelijke oplossingsrichtingen:

o herplaatsing in het park, dichter bij de voormalige Wide White Space gallery, mits akkoord van de kunstenaar,

o aankoop van een ander werk van David Lamelas als compensatie.

De kunstenaar ging niet in op de tweede piste, wel op het eerste voorstel voor een herplaatsing dichter bij de voormalige Wide White Space gallery.

De ontwerpers van Team van Meer, verantwoordelijk voor het tuinontwerp, maakten op vraag van de stuurgroep voor het masterplan van KMSKA een ontwerp nieuwe plaatsing. De kunstenaar ging akkoord met dit voorstel. -

Team van Meer raamde de heropbouw van de stalen constructie op 110.000 euro. Agentschap Onroerend Erfgoed gaf tijdens het vergunningstraject een negatief advies en naar verluidt hebben ook diverse stadsdiensten zich tijdens het ontwerptraject negatief uitgesproken.

In het voorjaar van 2020 besliste minister-president Jan Jambon op basis van deze gegevens het voorstel van een nieuwe editie niet te weerhouden.

M HKA begreep deze beslissing: er was geen budgetruimte binnen de enveloppe van KMSKA en het tijdspad voor heropening van KMSKA was nauw.

Er werd op dat moment vanuit de stedelijke overheid gedacht in termen van herplaatsing in het Middelheimmuseum, met veronachtzaming van de site- specifieke dimensie.

-

In juni 2020 had M HKA contact met de kunstenaar en toetste het alternatieve locaties elders op het Zuid af. De kunstenaar vond deze niet gepast. M HKA polste verschillende actoren binnen de stad om te kijken of van daaruit nog initiatief op korte termijn mogelijk was.

-

Op 28 augustus 2020 valideerde het schepencollege van de stad Antwerpen het, door Vlaanderen aan hen voorgelegd, definitief ontwerp van de tuin (zonder een nieuwe editie van het kunstwerk). Daarmee was er een basis voor de volgende stappen binnen de heraanleg van het park: vergunning, afspraken over periodiek groenonderhoud, publieke aanbesteding. De start van herinrichting van het park werd vastgelegd op februari 2021.

-

Op 18 september 2020 verstuurde de kunstenaar een mail naar de minister- president waarin hij de wens uitdrukte dat het werk op de site bewaard zou blijven.

-

Op 21 september had M HKA een - eerder geplande maar uitgestelde - afspraak op het kabinet van de minister-president. In een nieuwe nota argumenteerde M HKA naar de minister-president de wenselijkheid om toch tot herplaatsing over te gaan en bood het aan de productie hiervan op zich te nemen. De minister-president ging hierop in, maar vroeg expliciet akkoord van KMSKA.

M HKA kreeg meteen positief gehoor van KMSKA, zowel van de voorzitter van de Raad van Bestuur ervan als van de directrice, en ook van de stuurgroep Masterplan KMSKA. De vastgelegde werken aan de tuin werden vanzelfsprekend wel niet stilgelegd. Er werd beslist dat de noodzakelijke afbraak van de huidige editie van het kunstwerk in overleg met M HKA zou worden gedocumenteerd, in functie van de productie van de nieuwe editie.

-

November 2020: M HKA is inmiddels gestart met de productie- voorbereidingen. Het zal daarbij parallel verschillende uitdagingen moeten aangaan: de afbouw van het werk superviseren, de herplaatsing zelf concretiseren, de financiële middelen vinden en de vergunningen van de stad verkrijgen. Naast deze praktische stappen wenst M HKA ook inhoudelijk te werken door het plannen van een presentatie en diverse evenementen die het kunstwerk verder kaderen binnen een kunst(historische) perspectief maar ook binnen een vernieuwd maatschappelijk draagvlak.

Het aanschrijven van de minister-president is in deze dus niet langer relevant. De zorg voor het werk Quand le ciel bas et lourd ligt momenteel eenduidig bij het museum dat eerder al inzet toonde en de wens uitdrukte en om zich er voor te engageren. M HKA weet zich daarin niet alleen staan, en wordt nu ook gesterkt door het brede draagvlak dat uit deze brief blijkt.

Afbraak in februari komt er hoe dan ook, herplaatsing in dezelfde zone van het park binnen afzienbare tijd als het aan ons ligt ook.

Met u vinden we dit een uitzonderlijk werk en een sleutelwerk op diverse vlakken. We zullen u verder op de hoogte houden van dit spannend verhaal en u er graag zoveel mogelijk bij betrekken.

Met vriendelijke groet,

Bart De Baere, Directeur

(bron: https://blog.muhka.be/een-toekomst-voor-quand-le-ciel-bas-et-lourd-open-brief-van-bart-de-baere/)

Letter from David Lamelas and Jan Mot to Bart De Baere (15/12/2020)

M HKA

Bart De Baere

Brussels, 15 December 2020

Dear Bart,

Last Friday you wrote an Open Letter regarding the work Quand le ciel lourd et bas of David Lamelas. David and I wish to react to this briefly.

First of all our thanks for giving a chronological overview of different facts relating to the situation we are dealing with. It is certainly helpful for a better understanding as most elements you mention had never been communicated to us in writing before. The letter clearly shows your commitment to saving the artwork. It also mentions that you have managed to convince the Minister- President of the importance of the work with the result that you can now undertake the production of its new iteration. We are of course very happy with all this.

Equally important in your letter is that the new Director and the President of the Board of the KMSKA (both in CC) have responded positively to our wish to keep the work on the site of the museum. We would like to thank both of them for their support.

Towards the end of your letter you reveal your plans to work substantively by organising various events that will further situate the artwork within an art historical perspective. We welcome this too as we expect that this will create an even broader support for the work.

Your letter is written in a positive tone and David and I acknowledge that some aspects have developed in a good direction. But one crucial aspect of the whole project, namely the financial responsability, remains critical and simply unresolved. The Minister-President created an opening by allowing you to organise a new production but at the same time refuses to allocate the necessary budget. Moreover, I understood from our conversations and from your letter that the M HKA doesn’t have any budget to pay for this, even partly, and still needs to develop a strategy to find the financial means. So at this moment the future of David’s work remains very uncertain and we are still very worried.

Let us not forget that the problems we are facing have arisen independently from our will or influence. And that the work at M HKA’s request was donated by the artist in the understanding that a public collection would take care of its conservation. In your own argumentation towards the Minister-President you have stressed the historical and artistic importance of David’s work. The work is part of the Flemish patrimonium and a key reference work in your collection.

Let us also not forget that the current situation is the result of a serious mistake in the development of the new entrance. The calculations of the turning circles for the trucks that you mention in your letter should have been made at the very beginning of the renovation works and not in 2018. This way one would have had a choice: either create the truck entrance on the opposite site of the building and keep David’s work on its original location. Or anticipate the costs for the relocation and include them in the general budget of the renovations.

Given all these elements, it is clear to us that the Flemish authorities have a responsibility to make sure that this work of art will be saved on the original site but also to invest financially in its remake, even if it is only partly. We should not accept a situation where private funding is the sole source to protect the collection of your or any other public museum. Now that we have created a momentum with a significant public support we hope that you will once more reach out the Flemish Minister-President and convince him of his

responsibility. We believe that generously supporting this project will resonate positively and is the best way forward.

Thanks again for your support and all the best,

Jan Mot

PS 1: We will resend David’s initial letter to Mr Jambon, I owe this to the 840 people who have co-signed it.

PS 2: This letter will be added to the above mentioned letter.

Press

Art Monthly, Letter. Heritage and debt, Nr. 445, published April 2021

De Standaard, Historische tuin KMSKA wordt heraangelegd, published on 17/03/2021

De Standaard, Als erfgoed plots 'in de weg' staat, published on 22/02/2021

De Witte Raaf, 209, januari - februari 2021

HART Magazine, Werk van David Lamelas wordt weggehaald, published on 04/12/2020

Information on the work

David Lamelas

Quand le ciel bas et lourd (When the sky low and heavy), 1992

Installation consisting of metal sculpture and trees on inclined surface

Dimensions variable, metal structure: 6 x 20 x 7,8 m

View: Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp, 1990s

Photographed by David Lamelas

Initial proposal for the location of the work in front of the main entrance of the Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp (not realized). Drawing on photograph by David Lamelas reproduced in the catalogue: America. Bride of the sun. 500 years Latin America and the Low countries., 1991, edited by Pisters, I., Vandenbroeck, P., publisher Imschoot, Ghent, p. 244

The work can be described as a large sculpture built on an inclined surface and consisting of a trapezoidal shaped, steel roof under which 3 rows of 8 trees are planted. With time, the trees grow over the structure, almost hiding it, while other trees die because of a lack of light and water, leaving a void. The concept for this work was developed in several drawings and paintings during the 1980s when Lamelas was living in Los Angeles. But it was only on the occasion of an exhibition at the Royal Museum for Fine Arts in Antwerp, commemorating the 500 years of the so-called discovery of the Americas, that the work could finally be realised.

Quand le ciel bas et lourd is a work that deals with the relation between nature and the industrial society as well as with questions of oppression, struggle and censorship. As often in Lamelas’ oeuvre, it combines a conceptual and minimal aesthetic with political issues. Looking at Quand le ciel bas et lourd, two earlier works in particular by Lamelas come to mind. The first is his acclaimed film work The Desert People (1974) in which the question of the native American is central. Half road movie, half documentary, it portrays 5 young americans who speak about their experience of living with a tribe, the Papagos. The final monologue is by Manny, a Papago, who speaks in English, then Spanish and finally in Papago. The film culminates in a tragic car crash, as if the co-habitation of native and non-native americans is doomed. The second work is Dos espacios modificados which Lamelas made for the Bienal de Sao Paulo in 1966. In this piece he changed the shape of the cubicle that was given to him to show his work and doubled it by using aluminium beams and sheets, creating a second rectangular space without walls. Just like Quand le ciel bas et lourd, it plays with perspective and the point of view of the beholder as much as it raises the question of our spatial experience and understanding.

David Lamelas, Quand le ciel bas et lourd.

By Benjamin H.D. Buchloh

This text was published in the exhibition catalogue 'America. Bride of the sun. 500 years Latin America and the Low countries', p. 243-244.

In the extreme polarization between the urge to equate aesthetic operations with factual information and the withdrawal into selfreflexive tautological thought that defines conceptual art at the end of the 1960's, David Lamelas chose to occupy a position of deliberate undecidability, continuously shifting between the linguistic dimensions of structure and reference. Already in his first exhibition in Europe in 1968, when he represented Argentina at the XXXIV Venice Biennale, his installation at the pavilion circumscribed both the limitations of the tautological model of modernist self-reflexivity, and the limits of the institutions of art. By introducing the continuous flow of information on the developments of the Vietnam war supplied by news agencies and a telex machine into the pavilion, he turned the exhibition space literally into a newsroom: a secretary read the incoming news via a microphone to the viewers and recorded them simultaneously on a tape recorder for the entire duration of the exhibition (60 days), thus constructing a sedimentation of factual information and an exact historical record of the time period during which the 'work' and the 'exhibition' occurred and in which they literally coincided.

Entitled Office of Information about the Vietnam War; at three levels: the Visual Image, Text and Audio, both the complexity and the didactic clarity of Lamelas' work frustrated traditional aesthetic expectations and led to a relative failure of signification for the art world audiences of that moment. The installation ruptured first of all the discursive framework of conceptual art by introducing a model of language as communicative action, rather than a model of language as self-reflexive structure or as one of irrecuperable difference. [When Hans Haacke shifted at about the same time within his own development towards this radically different language theory, his work was met with equal scepticism: in fact one of his earliest explicitly political works, his contribution to the Prospect exhibition at the Kunsthalle Dusseldorf in 1969, constructs an almost identical integration of a seemingly formal procedure with a radically different set of language operations introduced into the institutional framework]. And at the same time the installation criticized the institutional framework of art by challenging the self-declared silence and the neutrality of the exhibition (literally by invoking sound as an aspect of representation, and metaphorically by activating the space as a function of information). In linking the exhibition/institution directly with the functions of public and political information and communication, Lamelas constructed not only a dialectic between the aesthetic and the factual, but he also reconstituted the lost political dimension of artistic institutions, reminding us of their origins in the bourgeois public sphere.

Beyond these obvious challenges the work posed a number of questions (perhaps not only unanswerable, but even inaudible at the time), questions not just concerning the relationship between the 'disinterested' aesthetic structure and the institutional frame, between linguistic self-referentiality and the instrumentalized languages of ideology and 'information·, but the work confronted its audience with the challenge of a Western hegemonic institution by an artist from the cultural 'margins' of Latin America, which seems to have been another reason why the work was 'overlooked' at the time.

Clearly the work must have provoked the defence mechanism of Western art audiences to protect themselves, first of all, against political questions as a matter of aesthetic principle. If, however, a political critique was articulated by a member of an unknown marginal artistic community, it had to be dismissed all the more urgently since the legitimacy of challenging Western hegemony itself had to be refuted. [In the same manner that David Medalla's work at Documenta V in 1972 remained largely 'unseen', since it constituted in a very similar way a contestation of the credibility of Western hegemonic culture by an artist from a 'third world' country.] Looking at Lamelas' work now makes us realize (more then twenty years after its definition) that in the audience's resistance, behind the guise of an aesthetic concern for high cultural purity and disciplinary autonomy, there operated an actual insistence on hegemonic superiority and the legitimation of continued ideological and political domination.

A second work, produced a year later for the Camden Arts Centre in London, raises a similar range of questions, and once again its relative obscurity reveals the inability of audiences and critics of the Sixties and Seventies (let alone those of the following generation) to situate Lamelas' work in an interpretative context.

Invited to install an exhibition at this institution, Lamelas suggested instead to use the available resources for the production of a short black and white film, entitled An Investigation of the Relations between Inner and Outer Space. The very substitution of a film production (modest as it was in terms of technology and budget) for an exhibition project, appears now as a programmatic decision in favour of a radically different perspective on both the institutional framework, the technical means of production and the distribution form of the work. As in his Venice Biennale installation in the preceding year, Lamelas deployed relatively advanced technology (film and sound recording) within the space traditionally reserved for static high art objects. However, it was a functional and communicative technology that was deliberately not neutral and value free, but that stood in almost programmatic opposition to the futile emphasis on traditional industrial production in 'minimal' sculpture where the discrepancy between industrial technology and the high art discourse of sculpture had ultimately remained on the level of a design problem. We should remind ourselves that in the mid-Sixties, with the minimalist's widely celebrated 'advanced' methods and materials of industrial fabrication for sculpture, one was in fact confronting a rather naive and romantically limited integration of industrial production within the high art object. By contrast, Lamelas deploys not only film and video technology as the primary media for his exhibition substitute, but he also uncovers within the film itself a catalogue of technologies that determine daily life in a very substantial and possibly complete manner: starting once again from an almost parodic performance of modernist self-referentiality by measuring the entire space of the exhibition and making the camera travel along all of the neutral white architectural surfaces that constitute the exhibition space, the film lists in a lapidary, almost statistical litany, in ever widening circles, the spatial and technological, the social and the institutional spheres that constitute the viewers' social identities - just as much as that of the subjects depicted in a shared continuum of technologies, urban organization, media technologies and transport systems. The film concludes in an almost grotesque climax, expanding the oppositional concepts of inner and outer space to a literal pun : a series of casual interviews conducted with anonymous pedestrians - by accident and foresight - on the day of the first manned landing on the moon (which happened to be the day the interviews were filmed).

It is against this factographic and political background of Lamelas' early works that one should consider the new sculptural installation at the Royal Museum of Fine Arts in Antwerp so as to resist an all too easy metaphorical reading, a disorientation that the work's conception seems to have consciously laid out for the viewer. The sculpture seems to appear at first like a renewal of late 1960's Arte Povera aesthetics and devices, almost as though aesthetics' structural juxtapositions along the axis of nature/culture opposites had crossed over into outdoor monumentalization, a tendency - it is crucial to emphasize here - that Arte Povera had been careful to avoid. Yet it soon becomes evident that the readmission of more traditional rhetorical forms (such as metaphorical constructions) in Lamelas' work is not merely the tribute to the newly conventionalized practices of art production, nor does it seem to be the price paid by an artist (who had turned his back on traditional artistic production procedures and distribution forms from the very beginning, and who has produced mostly film and video work over the last twenty years) to be readmitted into the institution of art and its traditional categories - even though it seems that sometimes no price might be too high to open the doors of the Museum to the present. But just as unconvincing would it be to argue that the enigmatic installation of a field of trees that will grow up under a shield of steel hovering over them like a shadow of extreme protection inevitably thwarting growth, eventually deforming and crippling them (in the way that traditionally in aristocratic horticulture fruit trees were grown in decorative formations like the espalier) would inscribe itself within a fairly recent tradition of sculptural works that - out of ecological concerns with romantic/remedial intentions - have incorporated trees or micro-ecologies into the conception of sculpture: from Joseph Beuys' 10,000 Oaks at Documenta VI in Kassel in 1978 or Michael Asher's proposal from the same year to plant an alley of trees instead of constructing large outdoor monumental sculptures for the urban sculpture renewal exhibition in Munster, onwards to the more recent works by Katharina Fritsch or Meg Webster. It seems rather that Lamelas' work constructs a particular historicist hybrid of the two sculptural conventions that of a romanticization of the simplicity and universal availability of natural means and resources as sculptural raw materials, as for example in the work of Richard Long, and, that of the continuing (and increasingly hollow) rhetoric of large scale sculptural site specific projects produced with tremendous industrial means which lack the simple tools to recognize their inability to situate their claims as public sculpture in the ruinous public sphere. Lamelas' installation entangles these two - mutually exclusive - sculptural conventions, and positions them in an allegorical interdependence of failure : neither the heroic rhetoric of the industrial construction (its origins having become finally evident as the origins of ecological devastation), nor the remedial concerns of a romantic commemoration of nature (and its mere ecological tokenism), could serve any longer as paradigms for contemporary sculptural constructs without acquiring immediately the features of fraudulence. Lamelas' installation seems to accept the necessity of a return to the sculptural traditions of the 1960's as a inevitable presupposition for his allegory of these failed heroic paradigms, their abused and obsolete strategies returning into the present as an involuntary and solely credible 'esthetique du mal'.

David Lamelas: four projects for the public space (1992-2010).

By Pedro de Llano

This text was published in the gallery's Newspaper 117, May 2019.

A CORUNA, MAY 22 - To create a dialogue between the work of David Lamelas and On Kawara is a felicitous idea which pays homage to the artists. Less is more: with only two pieces by each artist, the show at Jan Mot (March-April 2019) triggered a series of connections and links which allowed us to better appreciate their respective projects. The exhibition dealt with time of course – a fundamental subject for both artists, which several writers already addressed in different places – and also showed other interesting issues such as the representation of cities, the relationships that people establish with them, and most significantly, the city as a meeting point and a space for friendship.

The city as an environment to get together is a key subject of one of Lamelas pieces exhibited at the gallery in Brussels: Antwerp-Brussels (People and Time). When he did this work in 1969 – barely a year after his arrival to London thanks to a British Council grant in order to study at Saint Martin's School of Art – Lamelas already had a dense group of friends all over Europe. In this work he portrayed nine of them – artists, dealers, curators and collectors with whom he collaborated on various projects – in a series of black and white images always with the same framing: three women and seven men, mostly walking towards the camera, with determination, in urban contexts in which they appear to be the protagonists. Indeed, they seem to be the sole human presence – except for the photographer himself and traffic. Seven years later, Lamelas did a similar exercise in Los Angeles with his LA Friends. The chosen mediums here were drawing and a slideshow. The city didn´t feature visually on this occasion but in a caption introducing the neighbourhood where each friend lived: John Baldessari, Santa Monica. Allen Ruppersberg, Hollywood. John Knight, Silver Lake, etc…

This leit-motif in the exhibition at Jan Mot with works dating back to the 1960s and 1970s, made me think of the relation of Lamelas with different cities in which he has lived and more particularly, of the projects for public space that he conceived throughout his career. In the 1990s Lamelas created a series of projects for public space which did not always receive the same attention as his “classic” works from the Conceptual years (1968-1975). It is important to recall that these projects don´t appear from scratch, but rather with deep roots in different pieces since the 1960s. For example in the second piece included at Jan Mot – Time as Activity – which began to exist in 1969 in this German city and currently counts up to eleven versions filmed in cities such as Berlin, Los Angeles or Madrid.[1] Or Señalamiento de tres objetos (1966-68), in which the artist intervenes in a public park transforming a tree, a streetlight, and a deck chair in artworks by surrounding them with rectangular metalic sheets laying on the ground that act as “frames”, enhancing them in their environment, creating a visual and spatial relationship among them, and with the passerby as well.

Projects in the public space became popular in the 1980s and 1990s and were a direct effect of the expansion of the artistic field provoked by Conceptual art in its crucial period between 1968 and 1975. Proof of it is the organization of the first edition of the Skulptur Projekte in Münster in 1977. Or Chambres d’amis, the memorable exhibition curated by Jan Hoet in Ghent in 1986, in which 50 artists conceived works for private homes, blurring the limits between public and intimate space. Both in Europe and the US these initiatives were essential for the understanding of the evolution of a whole group of artists who began doing immaterial and conceptual art in the 1960s (performances, films, language-based works, etc…) and who were marginalized by the market and many institutions in the neo-conservative era of the 1980s with the return of painting and object-based practices. Vito Acconci or Dan Graham are explicit cases, but also others, closer to David Lamelas in Los Angeles such as Allen Ruppersberg, Michael Asher, John Knight, Dorit Cypis or Maria Nordman – most of whom posed for him at the studio on Sunset Boulevard.

The 1980s were a sort of “desert crossing” for many of these artists. Nevertheless during this decade Lamelas did some of his best known videos in Los Angeles. In these works the city has a relevant presence, although not essential. The city plays more as a background than a leading role. However, video did have an incentive which we can also find in his projects for public space: it’s capacity to reach larger audiences.[2] After this period came another – in the second half of the 1980s – in which Lamelas returned to a practice which is central throughout his career but which stayed somehow in the shadow: drawing and painting. From this period are pieces such as Inside-Outside (1984), Entwurf “Reception Center for Solar Energy” (1986) and Los Angeles PM (1987) in which Lamelas experiments with apparently traditional mediums, but with innovative and original intentions. What is especially interesting in some of these works is the idea of a project carried out through drawing and/or painting. We can see this for instance in a work like Entwurf “Reception Center for Solar Energy” (1986) – a sort of sketch for a utopian and deliberately inconcrete ecological initiative which nevertheless turns out to be evocative of the “New Age” trends to which some Southern California artists gravitated in the 1980s. And this brings us straight into the 1990s projects, in which drawing as a conceptual tool appears, together with writing, as a genuine constant in the work of David Lamelas – from the earliest to the very recent.[3]

* * *

The first project I’d like to focus on bears the poetic title Quand le ciel est bas et lourd (1987-92).[4] It was produced for the group exhibition America. Bride of the Sun. 500 Years of Latin America and the Low Countries and consists of a hovering steel plate in the form of a trapezoid, suspended by three rows of eight pillars. Under the plate Lamelas planted three rows of sycamore trees which seem to converge toward an imaginary vanishing point. The piece was installed in 1992 next to the Museum of Fine Arts in Antwerp (designed by Jacob Winders and Frans van Dijk and opened in 1890) in a surrounding park and opposite of the former location of Wide White Space, Lamelas’ first Belgian gallery., The structure functions as an asymmetric element – dynamic and relatively unstable that contrasts both with the solemnity of the Neo-classical building of the museum and the rationality of the urban axis of the Flemish city which is known in the Zuid neighbourhood as “The Petit Paris” – a reference to Baron Haussmann.

Benjamin Buchloh points out the monumental and architectonic character of this work, as opposed to the immateriality of his previous projects – especially those related to video and TV.[5] The title is borrowed from the first verse of a poem by Baudelaire and intends to be a commentary about the so-called discovery of America (which had its 500 years celebration in 1992), and the oppression suffered by the American peoples (indigenous, slaves, immigrants…) since colonial times until the imperialist episodes of the Cold War, and through the different processes towards Independence in the 19th century.

This particular work has a changing life: in the earlier pictures it’s possible to see the growing young trees sheltered under the metal plate at the same time that limited and perhaps impeded by the lack of light. In other, more recent images, the work seems to “disappear” or hide out: trees – at least those in the lateral rows – have overtaken the structure and grown all over and above. This process reproduces, in an abstract, organic and visual way, the struggle for liberation and emancipation of the American peoples after 1492 – a dialectic in which some win and overflow the imposed limits, conquering freedom, while others loose and stay subjugated and underdeveloped (that´s to say: there were Americas which were more “brides of the sun” than others). Finally, Quand le ciel est bas et lourd reminds us as well of an unrealized project by Bruce Nauman from the late 1960s in which he also intended to put a plaque on top of a single growing tree: “After a few years, the tree would grow over it”, Nauman declared in an interview, “and finally cover it up, and it would be gone”.[6] Despite the formal similitude, the intentions and content of both artists are very different. In the context of the current general rehabilitation of the premises of the Museum of Fine Arts, Lamelas’ work will soon be dismantled and reconstructed in the same park close to the original location.

In 1996, four years after the Antwerp piece and amidst of the rise of public sculpture, Lamelas built Vivienda (Structure) in the city of Santo Tirso, north of Oporto in Portugal. This work was commissioned by the Museo Internacional de Escultura Contemporânea de Santo Tirso; a project dedicated to public sculpture, propelled in its origins by the Portuguese artist Alberto Carneiro – whom Lamelas met at Saint Martin´s at the end of the 1960s. The work was first conceived as a model titled Vivienda (Living Space) and it consisted of a structure which makes us think of the archetype of the house; that is, reduced to its minimal elements – four walls that don’t touch each other, a door, and a roof. There are differences, however, between the project and the finished work. In the first, we see a living place with leaning walls. They need wooden beams to shore the walls up and to prevent from collapsing. It’s indeed a house on the verge of falling apart which brings two references to mind. One by Lamelas himself: his work Untitled (Falling Wall), which he first presented at the Galeria Fac-Simile in Milan, 1993, and a second one of different kind; the infamous scene in a 1920s Buster Keaton film in which the façade of a house falls over the actor – miraculously escaping injury.

In the final version of the work the walls have disappeared and are replaced by a diaphanous metal structure and again surrounded by trees as in Antwerp. The piece is located in the Jardim dos Carvalhais next to a panoramic lookout to the landscape. In the realised version, the house maintains the original scale and volume, as well as the comic detail of a useless door, but it´s been reduced to a sort of sketch or drawing in the air which reflects the dynamism of the first idea, in a different way, together with a certain will to deconstruct the notion of “home” which was also present in the beginning. Is this perhaps the home of a nomad like David Lamelas? Or a gathering point to celebrate a picnic with friends?

While Lamelas was installing the work, he noticed its potential to become a rendez vous for locals and visitors. That’s why in some of the earliest images a pink marble stone bench is missing – which was later added to the work in order to foster its “use”. The idea worked and shortly after people appropriated the sculpture, especially retired men who would meet there to chat and play domino. This characteristic of Lamelas’ work for the public space –its “use value” – wasn´t that common in the mid-1990s. It was probably the Skulptur Projekte in Münster a year later, in 1997, which made widely known and accepted this kind of projects in between sculpture and design, even if some artists like Dan Graham and Maria Nordman were experimenting with these ideas already in the 1980s. Lamelas points out that his work in Antwerp also has this feature. As neighbours got used to it they started to give it different functions: as a protection from the rain, a shelter for people walking their dogs, a hide-out for couples making out…

Nevertheless, the functional or interactive character of Lamelas’ public works is never literal but rather at some point between its practical use and the symbolic meaning. A good example is an unrealized project with a critical content which seems even more poignant today. It was one of the proposals he sent to the curators of the Biennal In Site, in Tijuana in 1997 and was discarded. The idea would be to build a temporary structure which would act as a stairway and lookout at the same time. From the top of the structure it would be possible to see the US from the Mexican side – the “promised land” for migrants. This proposal involved some degree of irony: paradise can be seen but not touched, shown but not shared. As the son of Spanish immigrants himself, Lamelas tried to evidence, through humour, the injustice which walls and all sort of obstacles represent and impose for those seeking to reach their wishes and access a better life.

After 2000 Lamelas became less involved with projects for public space, at a time the genre itself got into a crisis and the artist entered a new phase in his career. Still he didn’t abandon this kind of practice completely and in February 2010 he accomplished a new piece – very different to the ones before – in Los Angeles. The work was entitled Think of Good and was developed for the group project How Many Billboards, a MAK Center and Schindler House initiative. In this case, his proposal was to revisit one of his most emblematic works: Rock Star (Character Appropiation) from 1974. He re-enacted the photo shoot with a professional photographer, himself posing as an “aging rock star”. On this occasion he edited only one image – worth of Mick Jagger at his best – full of attitude, grabbing a mic, hair slicked back and defiant look. This image was enlarged and printed on the monumental size of a typical Los Angeles billboard, together with the text “Think of Good” – which could well have been taken from one of those self-help, “New-agish”, positive thinking advertising assumed to be characteristic of Southern California culture.

The piece was installed at Pico and Fairfax, two main Los Angeles thoroughfares, halfway from the studio he rented in Sunset Boulevard when he arrived to LA in the 1970s, and Venice where he lived in the 1980s. In fact, both places are symbolically linked to the content of the image: Sunset because it was not far from the Strip, the rogue neighbourhood where all the rock stars performed back in the day at clubs such as the Starwood or English Disco, and Venice, where Gold´s Gym – the iconic fitness center funded by Arnold Schwarzenegger – used to be, becoming an inescapable meeting point for the still bohemian community to which Lamelas belonged, striving to retain youthfulness and fitness with the weight and running machines.

Think of Good is certainly a singular piece because it emphasizes image and representation more than the architectural and participative pieces from the 1990s. Still, all these works share a common approach in which humour and bits of absurdity are fundamental to create a precise and critical relation with urban space. This set of realized and unrealized projects constitute an important contribution to the genre of public art and they let us see David Lamelas work from a different perspective.

Pedro de Llano is a curator and postdoctoral researcher at the University of Santiago de Compostela (ES).

[1] One of the most recent iterations of Time as Activity was shot in Athens and Berlin for the documenta 13, 2017. In Kassel was installed at the ICE station Kassel-Wilhelmshöhe, just in the platform through which the passengers left the train and went into the city.

[2] Lynda Morris, “David Lamelas’ Experience”, exh. cat., David Lamelas, Secession, Vienna, 2006, p. 19.

[3] It’s possible to note these relations between idea, drawing, project and materialization in many of his drawings from 1965 to 1967 – but even earlier than that in certain unpublished works.

[4] The works in public space by David Lamelas that I have been able to retrace are:

- Señalamiento de tres objetos (Signaling of Three Objects), Buenos Aires-London, 1966-68

- Screen, New York City, 1988

- Quand le ciel est bas et lourd, Antwerp, 1987-92

- Vivienda (Structure), Santo Tirso, Portugal, 1996

- A Bridge Between Two Trees , Zoersel, Belgium, 1996

- Unrealized project for in Site 97, San Diego and Tijuana, 1997

- Al otro lado (The Other Side), inSite 97, San Diego and Tijuana, 1997

- Think of Good, in the project How Many Billboards, Los Ángeles, 2010

- Time as Activity: Live Athens-Berlin, documenta 13, 2017

In 1996 David Lamelas created a second work in public space in Belgium, for a temporary exhibition in Zoersel, entitled A Bridge Between Two Trees.

[5] Benjamin Buchloh, “Structure, Sign and Reference in the Work of David Lamelas”, exh. cat., David Lamelas. A New Refutation of Time, München and Rotterdam, München Kunstverein and Witte de With, 1997, p. 144.

[6] Joe Raffaele and Elizabeth Baker, excerpt from “The Way-Out West: Interviews with 4 San Francisco Artists” (1967), published online by Artnews on March 16, 2018, in honor of Bruce Nauman´s retrospective at Schaulager Basel [http://www.artnews.com/2018/03/16/archives-bruce-nauman-fishing-surrealism-filmmaking-1967/ [Last accessed: May 14, 2019]

You can still show your support by co-signing the letter to Jan Jambon.

The list will regularly be updated.

KINDLY ENTER YOUR FIRST & LAST NAME, EMAIL, AND PRESS SIGN: