Joachim Koester

Current and upcoming

Chambres des échos

Espace d'art François-Auguste Ducros (a project by IAC Villeurbanne/Rhône-Alpes), Grignan (FR)

Exhibitions at Jan Mot

Sometimes when you blink you may see trees

Joachim Koester - Stefan A. Pedersen, sound pieces

Juliaan Lampens, daybeds

Jonathan Muecke, lamps

In collaboration with Maniera

Manon de Boer, Joachim Koester, Ian Wilson

Joachim Koester

The Place of Dead Roads

Joachim Koester

Reptile brain, or reptile body, it's your animal

Joachim Koester

I myself am only a receiving apparatus

Joachim Koester

Histories

Joachim Koester

New Works

Robert Barry, Manon de Boer, Pierre Bismuth, Daniel Buren, Douglas Gordon Joachim Koester, David Lamelas, Jonathan Monk, Mario Garcia Torres, Ian Wilson

Today is just a copy of yesterday

Joachim Koester

The Tools of My Trade

Eija-Liisa Ahtila, Sven Augustijnen, Richard Billingham, Pierre Bismuth, Manon de Boer, Rineke Dijkstra, Honoré ∂'O, Dora García, Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, Douglas Gordon, Joachim Koester, Sharon Lockhart, Deimantas Narkevičius, Uri Tzaig, Ian Wilson

New Space Opening Show

Joachim Koester

Row Housing

Joachim Koester

Nordenskiöld and the Ice Cap

Joachim Koester

Other exhibitions

Joachim Koester

If One Thing Moves, Everything Moves

Kunsthal Charlottenborg, Copenhagen

The Danish Pavilion

51st Venice Biennale, Venice (IT)

Works

Joachim Koester

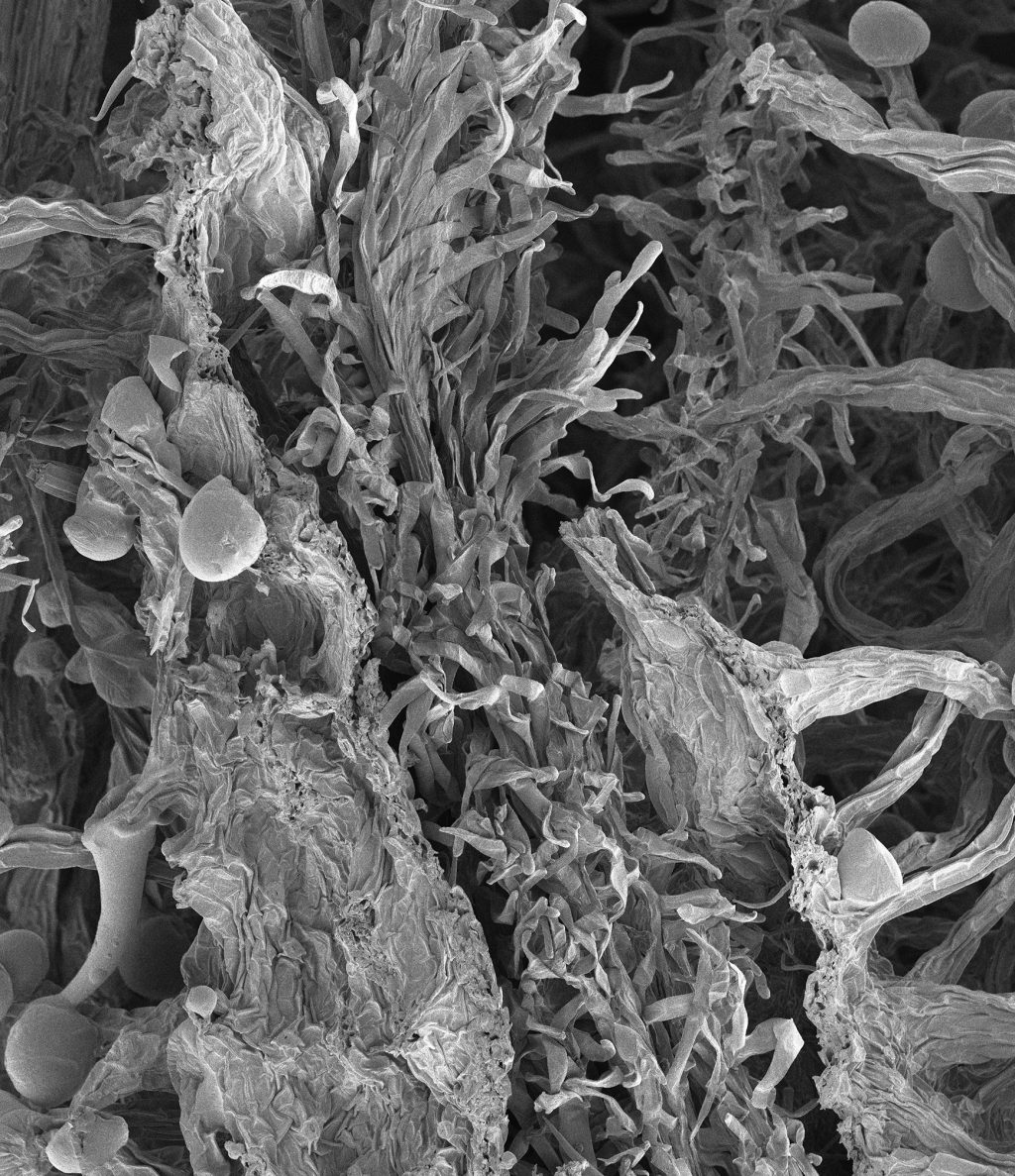

Cannabis #1, 2019

inkjet print

90 x 72,5 cm

edition of 5 and 2 A.P.

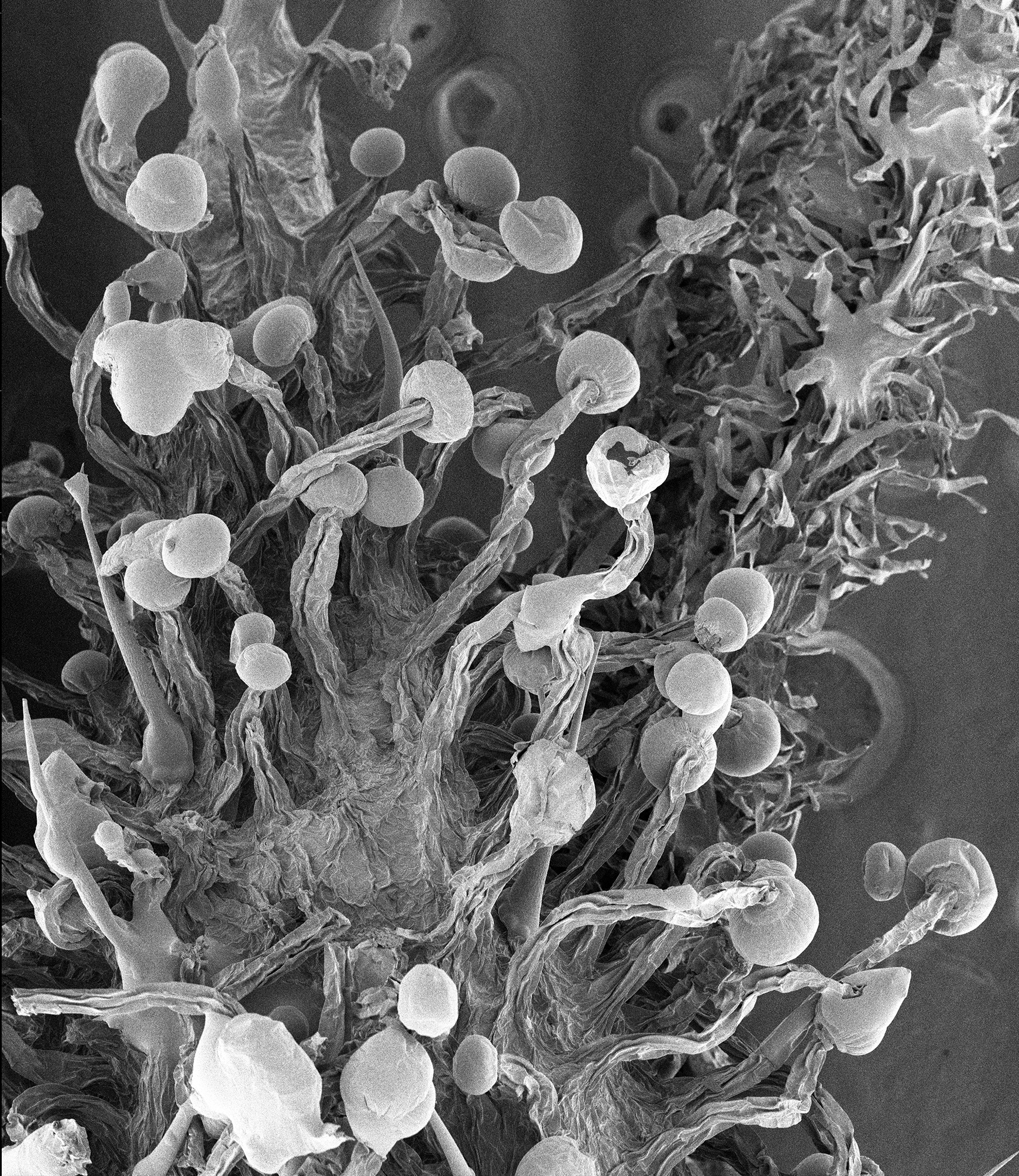

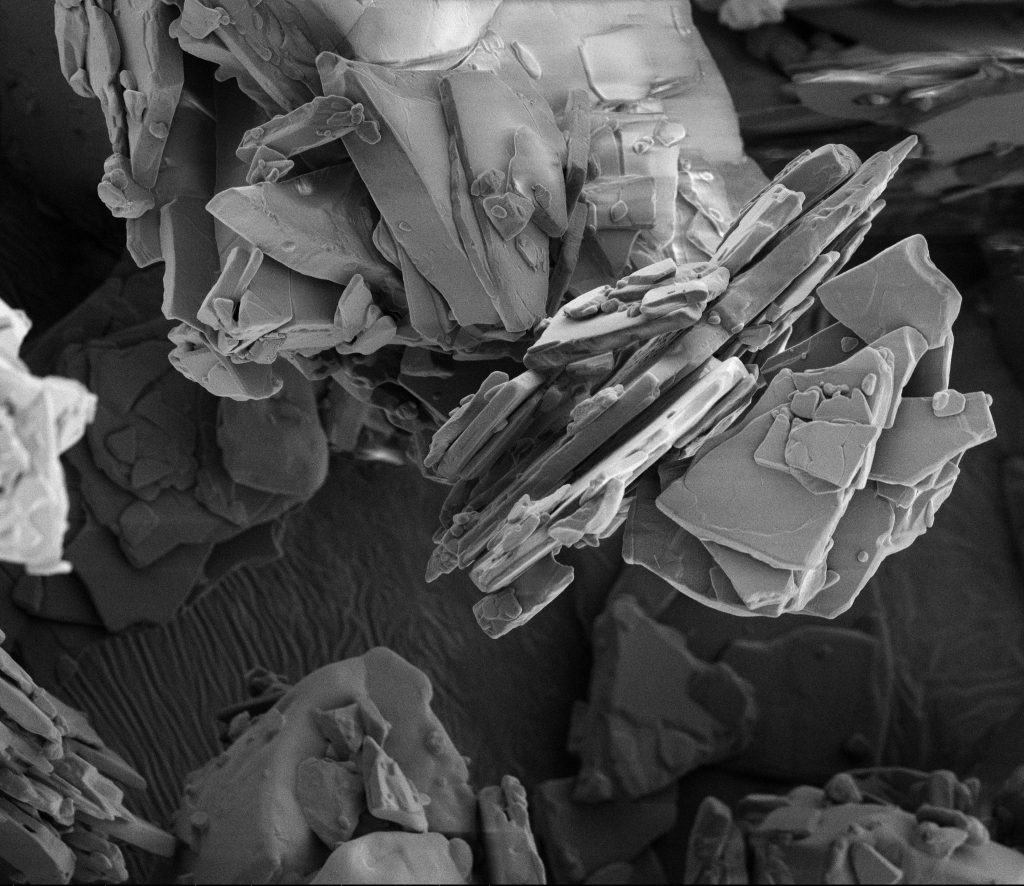

Joachim Koester

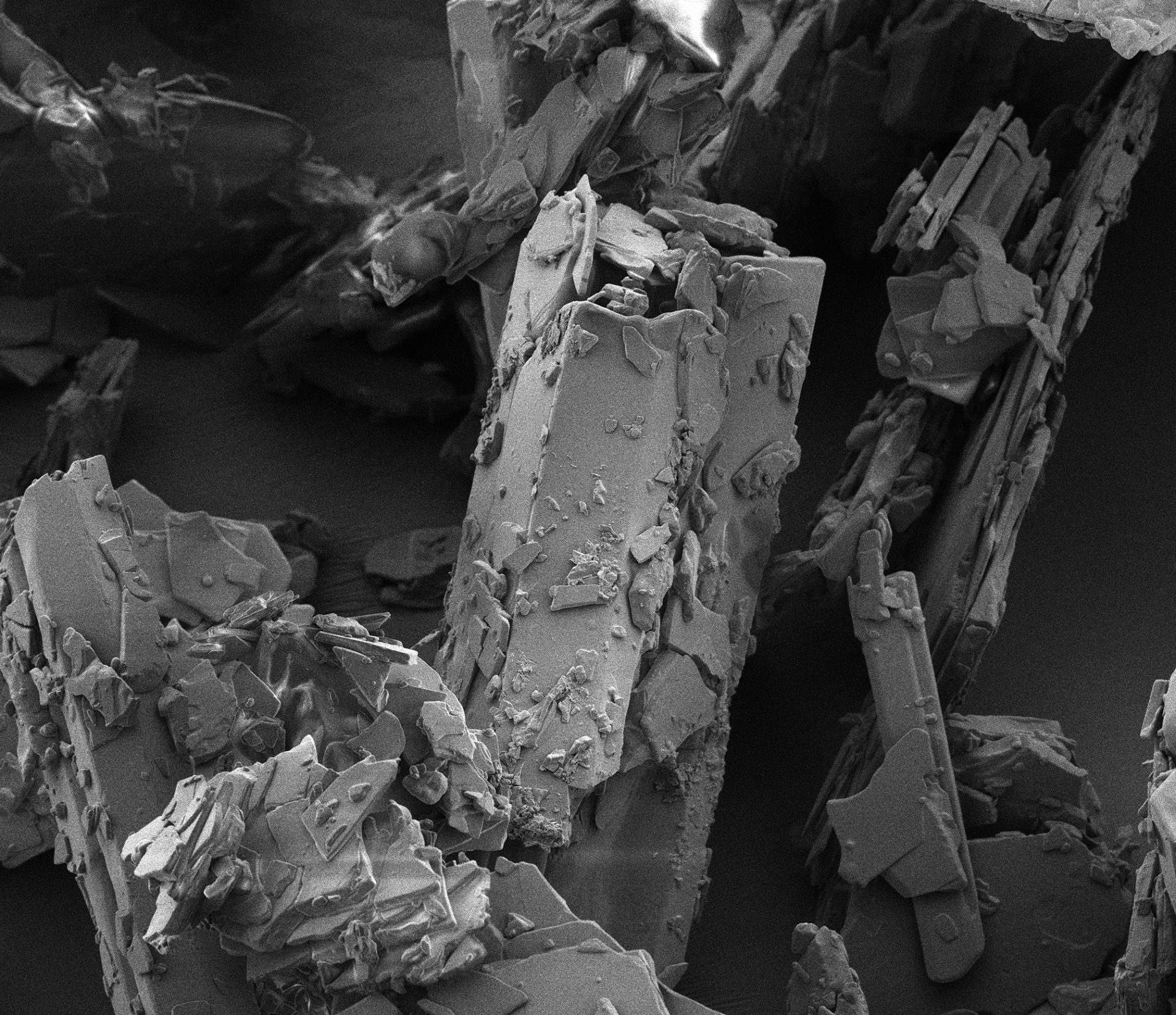

Cocaine #8, 2019

silver gelatin print

40 x 46 cm (image), 56 x 62 cm (frame)

Joachim Koester

Cocaine #6, 2019

silver gelatin print

46 x 40 cm (image), 56 x 62 cm (frame)

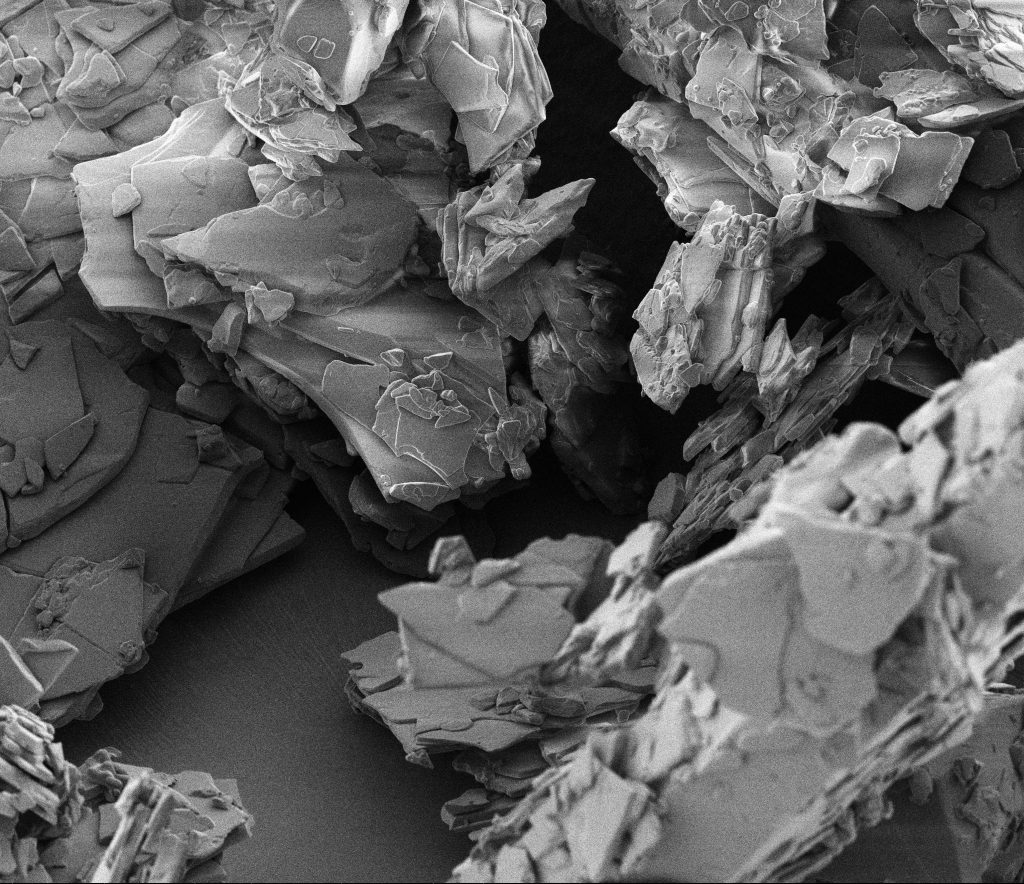

Joachim Koester

Cannabis #1, 2019

silver gelatin print

46 x40 cm (image), 62 x 55 cm (frame)

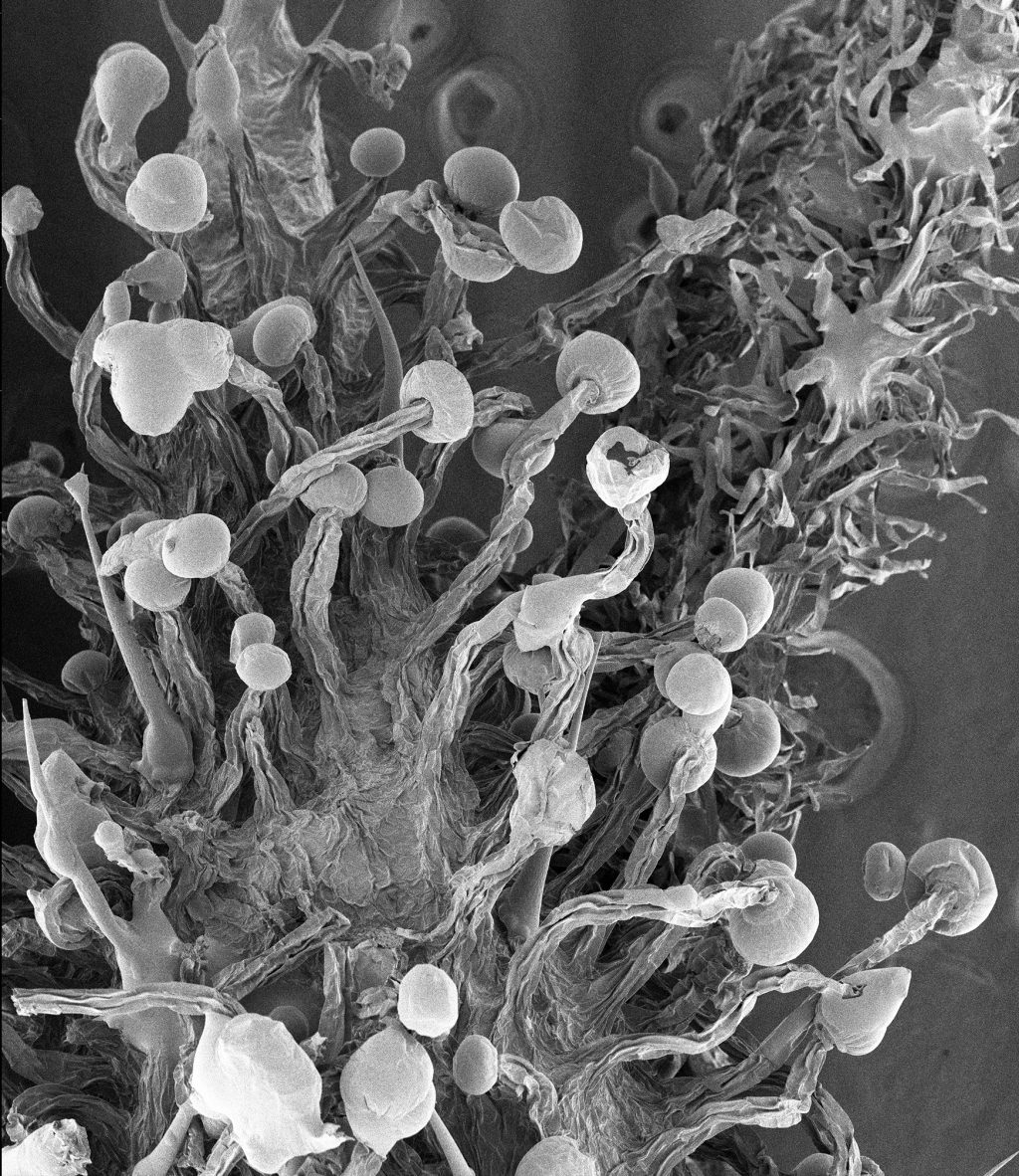

Joachim Koester

Cannabis SEM #3, 2019

silver gelatin print

46 x 40 cm (image), 62 x 55 cm (frame)

Joachim Koester

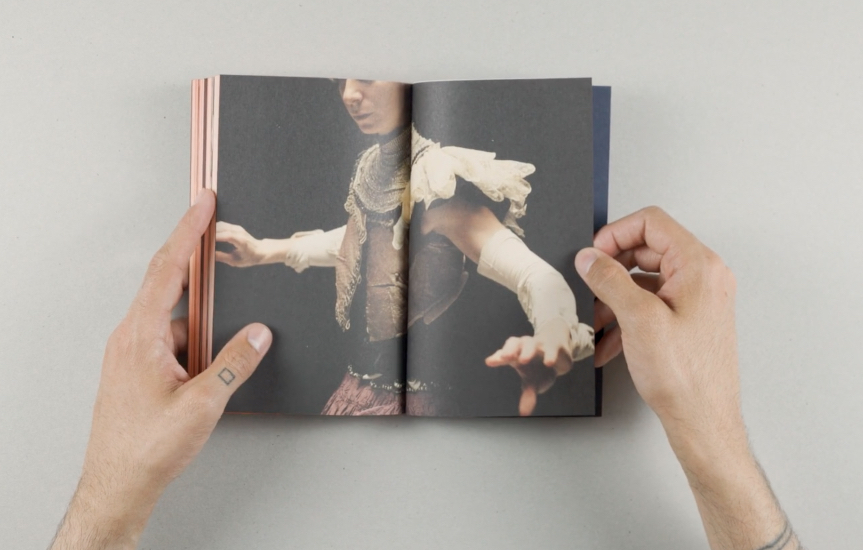

Maybe this act, this work, this thing, 2016

video, colour, sound

20 minutes

edition of 5, 2 A.P.

(excerpt)

Joachim Koester

H. Grandis (1), 2015

inkjet print, framed

112 x 87 cm (frame)

edition of 5 and 2 A.P.

Joachim Koester

Idolomantis diabolica (2), 2015

inkjet print, framed

112 x 87 cm (frame)

edition of 5 and 2 A.P.

Joachim Koester

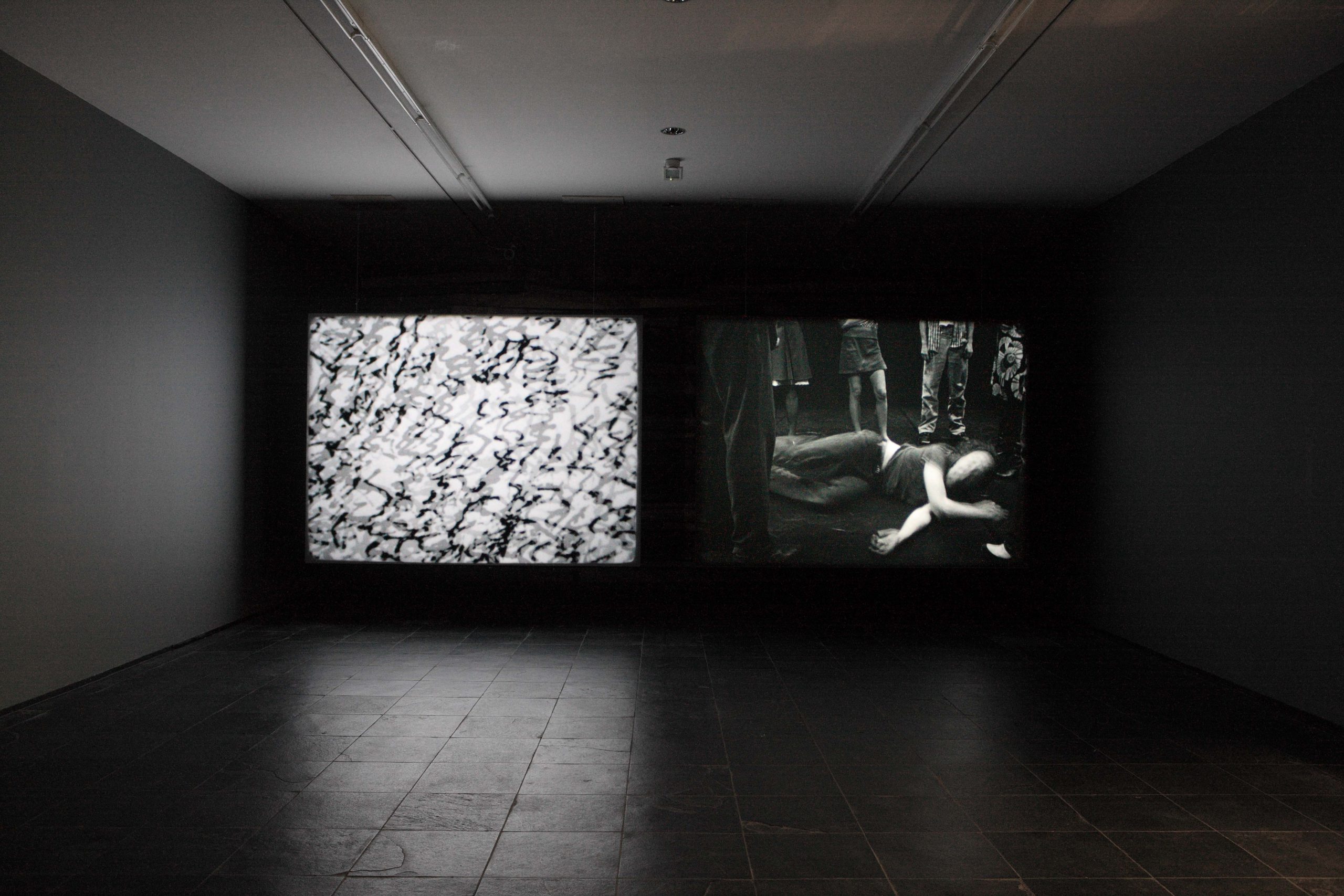

The Place of Dead Roads, 2013

16 mm transferred to HD video, color, sound

33 minutes 31 seconds

edition of 7 and 2 A.P.

(excerpt)

In the video installation, The Place of Dead Roads, four down-and-out androgynous cowboys engage in the ritual of posing, circling, drawing guns, shooting and other gestures linked to the Western film genre. Rather than being driven by a narrative, their actions are motivated by hidden messages transmitted from a world deep within their bodies. Gradually, as the cowboys engage in an exploration of these dark sensations, the jerks and involuntary movements of their actions come to resemble an odd kind of dance. The setting is a subterranean world that resembles a dust-ridden gold mine. The cowboys roam through this confused maze of underground hallways, rooms, and spaces.

I kept thinking of a quote by Wilhelm Reich while working on this project: “Every muscular contraction contains the history and meaning of its origin.” I'm probably reading something different into "history and meaning" than Reich would, but I find it interesting to see the drawing of guns in this context. The gesture becomes embedded as a memory and history on a micro muscular level. Staying within the Reichian terminology, The Place of Dead Roads also contains sparks of hope. The “happy dance,” the hypnagogic disco-like movements that occasionally take possession of the cowboys, can be seen as an attempt to end the spell of historic violence by breaking through what Reich referred to as “body armor.”

The title, The Place of Dead Roads, is derived from a William S. Burroughs novel about time-traveling gun slingers from the Wild West on a quest for immortality. Burroughs explained that roads are not dead because they are “unused,” but because they are "used by the dead." In my film, these “dead roads” are transformed into a “shadow realm,” a labyrinthine territory where the traversing cowboys compulsively repeat the gestures related to a shootout.

by Joachim Koester

Joachim Koester

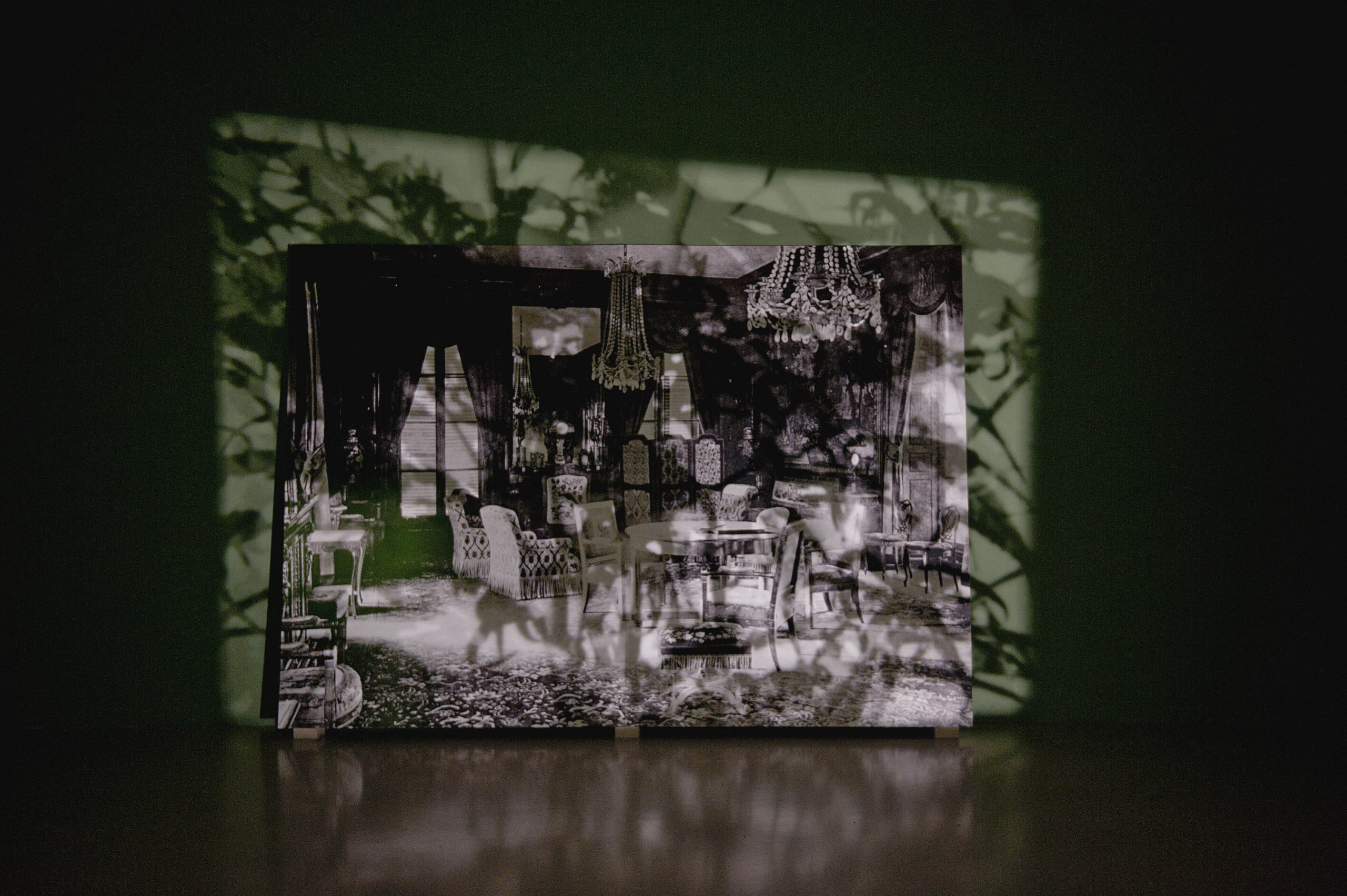

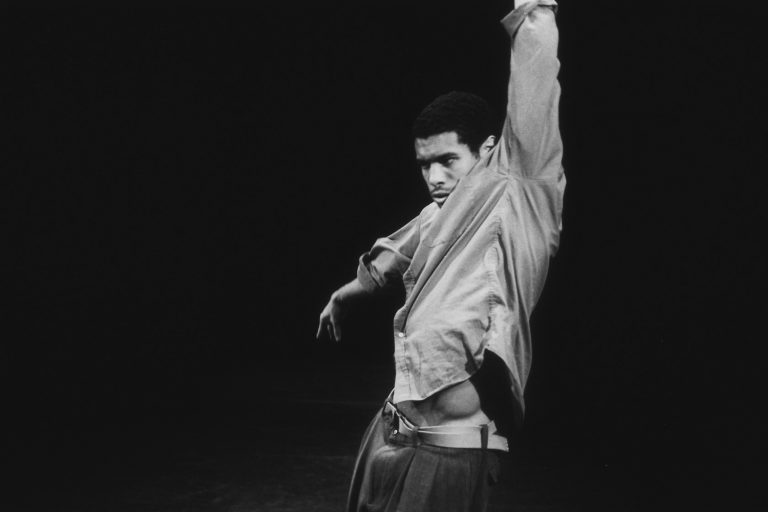

Maybe one must begin with some particular places, 2012

16 mm film, black and white, silent

2 minutes 48 seconds

edition of 5 and 2 A.P.

(excerpt)

In the late 1960s, the Polish theatre director Jerzy Grotowski abandoned theatre to create a system of “motions” and “spatial practices” that made him one of the main contributors to contemporary performance. Grotowski replaced the conventional structure of drama with improvised activities, games and a psychophysical system of exercises to train and refine the bodily and mental awareness of the actor.

Exploring the intersection of performance, anthropology and ritual, Grotowski developed works that would last for days or weeks. They would take place – often without an audience – at remote locations, like an old farmhouse in rural Poland, an abandoned castle or the deserts and jungles of Mexico.

Grotowski visited Mexico in 1968 and several times after that. During one of these trips, in 1985, Grotowski planned and directed a work involving 14 volunteers outside the city of Tepalcingo, Morelos. Like the charlatan shaman Carlos Castaneda, or the founder of the “Theatre of Cruelty” Antonin Artaud before him, the “wilderness” of Mexico became a scene to expand the boundaries of self and presence.

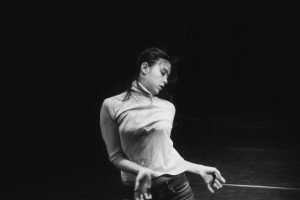

Grotowski’s “motions” and “spatial practices” make up an archive of gestures and ideas and engaging in this tradition is an evocation of its claims and promises. Maybe one must begin with some particular places is a film of Grotowski’s psychophysical exercises. The actor is Jaime Soriano, who also participated in the work in Tepalcingo in 1985, and the location is the terrace of the Luis Barragán House in Mexico City.

by Joachim Koester

Joachim Koester

Reptile brain, or reptile body, it’s your animal, 2012

16 mm film, color, sound

5 minutes 36 seconds

edition of 5 and 2 A.P.

(excerpt)

Joachim Koester

Some Boarded Up Houses (Baltimore #1), 2010

silver gelatin print

32,5 x 25,5 cm (image), 50 x 42 cm (frame)

edition of 3 and 2 A.P.

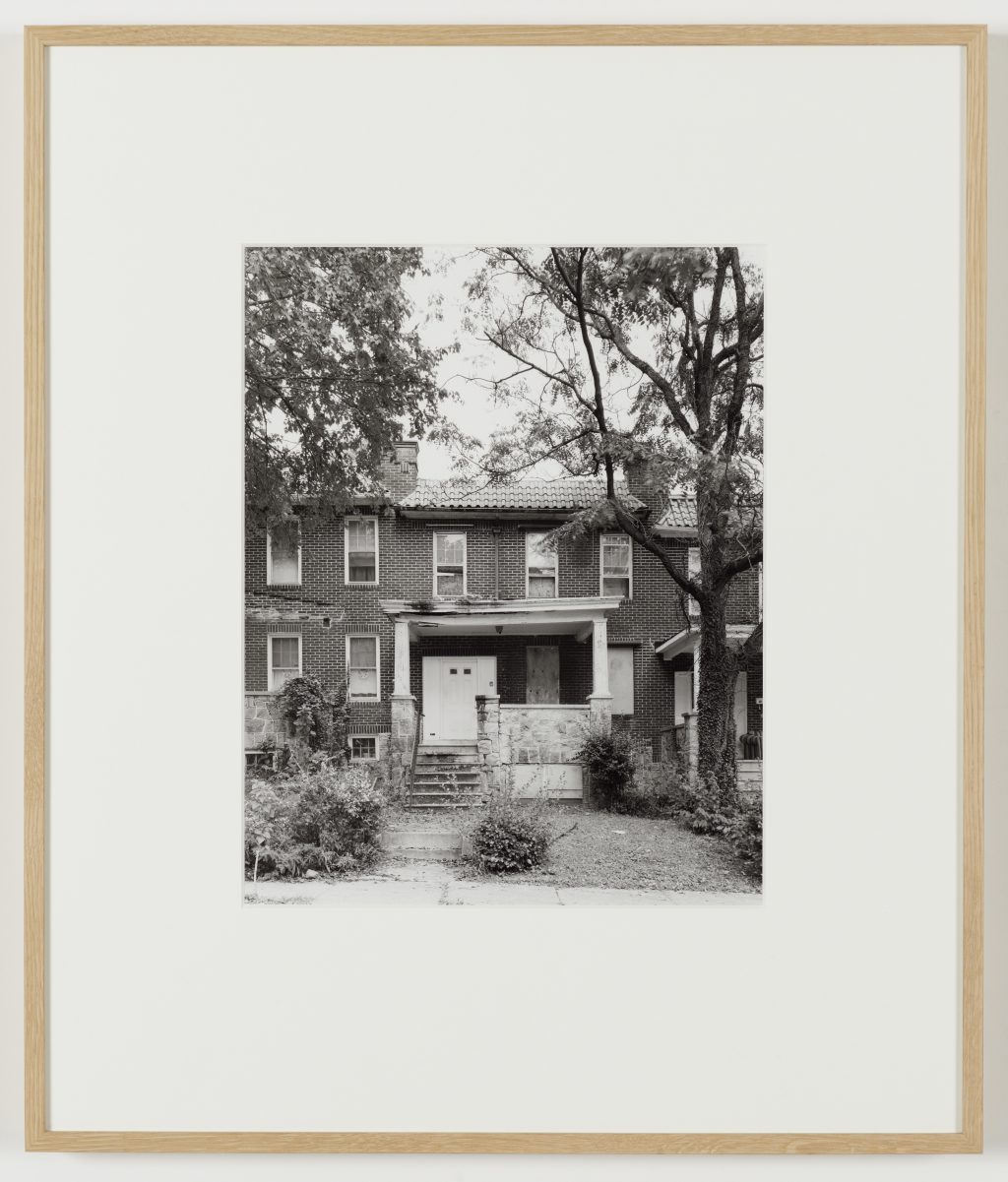

Joachim Koester

Some Boarded Up Houses (Baltimore #3), 2010

silver gelatin print

32,5 x 25,5 cm (image), 50 x 42 cm (frame)

edition of 3 and 2 A.P.

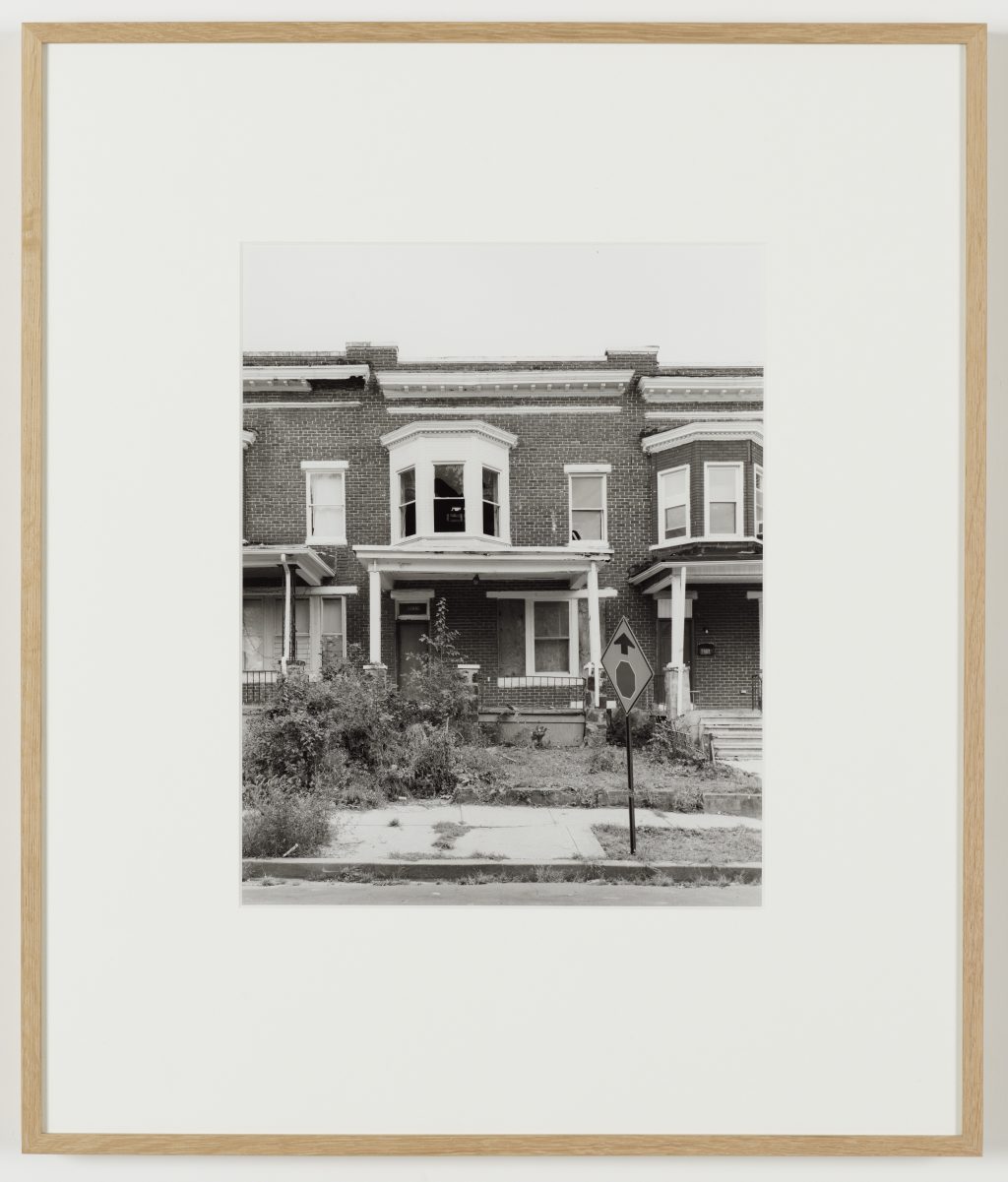

Joachim Koester

Some Boarded Up Houses (Baltimore #2), 2010

silver gelatin print

32,5 x 25,5 cm (image), 50 x 42 cm (frame)

edition of 3 and 2 A.P.

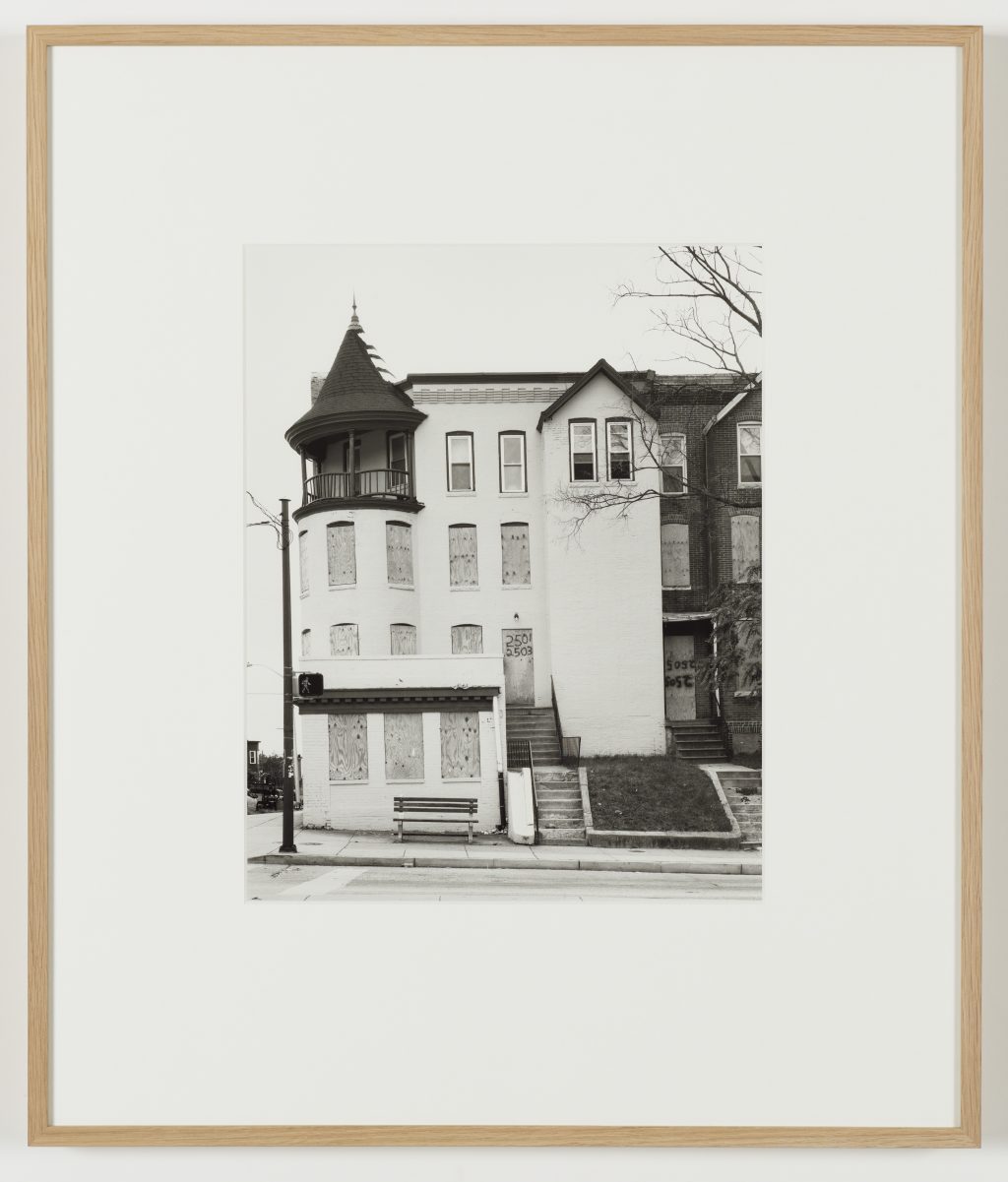

Joachim Koester

Some Boarded Up Houses (Baltimore #4), 2010

silver gelatin print

32,5 x 25,5 cm (image), 50 x 42 cm (frame)

edition of 3 and 2 A.P.

Joachim Koester

Variations of Incomplete Open Cubes, 2011

16mm film, black and white, silent

8 minutes 15 seconds

edition of 5 and 2 A.P.

In 1974, Sol LeWitt exhibited 122 variations on the theme of incomplete open cubes presented as sculptures, photographs and schematic drawings. Here, LeWitt continued his lifelong investigation of conceptual and serial procedures, creating a work that animates contradiction by deploying an idea to become a “machine that makes art.” Variations of Incomplete Open Cubes occupies a territory of objective, subjective, rational, compulsive and irrational exchanges. These are inscribed in the tension between the irreproachable system-like logic of its presentation, and the very premise of the “machine” itself, which seems to short-circuit necessity and reason. LeWitt writes that “conceptual artists are mystics rather than rationalists” and that “irrational judgments lead to new experience.” Perhaps the irrational “new experience ” produced by Variations of Incomplete Open Cubes and its machinery should be understood, apart from being something tangible, as a call to explore or lose oneself in the affective and critical terrain that makes the work and its reception. (J.K.)

Joachim Koester

Tarantism, 2007

16 mm film, black and white, silent

6 minutes 30 seconds

edition of 5 and 2 A.P.

Tarantism is a condition resulting from the bite of the wolf spider, originally known as the tarantula. The bite causes numerous symptoms in the victim: nausea, difficulties in speech, delirium, heightened excitability and restlessness. The bodies of the bitten are seized by convulsions that previously could only be cured by a sort of frenzied dancing. Even the Bishop of Polignano, who in the seventeenth century allowed himself to be bitten to disprove the cure, felt compelled to dance to relieve his symptoms.

This “dancing-cure” called the Tarantella emerged during the Middle Ages as a local phenomenon in and around the city of Galatina, in southern Italy, and was widespread in the region up until the middle of the twentieth century. Since then, the Tarantella has evolved from a form of uncoordinated movement – where people would “quiver and hurl their heads, shake their knees, grind their teeth and make the actions of madmen” – into a highly stylized dance for couples.

My interest in tarantism is tied to its original form: a dance of uncontrolled and compulsive movements, spasms and convulsions. In the film I have utilized this idea to generate the movements of the dancers. In six individually choreographed parts, the dancers attempt to explore a type of grey zone: the fringes of the body or what might be called the body’s terra incognita. (J.K.)

Biography

Joachim Koester

Born in Copenhagen in 1962

Graduated from the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts in 1993

Lives and works in Copenhagen

View full biography

Bibliography

News

Simultaneously with his show at the gallery, Joachim Koester's solo exhibition at Museum Dr Guislain opens on Saturday 20/03. The exhibition titled Altered States brings work together that investigate unknown territories, both geographical and mental. An ‘altered state of consciousness’ refers to a temporary change in the mental state. The cause is often external, such as a drug or a ritual, but also internal, such as a psychosis or simply a daydream. Koester shares his fascination with the effect of intoxicants with shamans and hippies, but also with psychiatrists. The latter recognised the therapeutic possibilities, but they were also confronted with the destructive power. Joachim Koester’s work delves into the historic context in which drugs were grown, traded and used, and draws parallels with the contemporary situation. Big and small stories impartially reveal our relationship with intoxication.