15/12/2021 - 05/02/2022

Edouard Merino

Insights

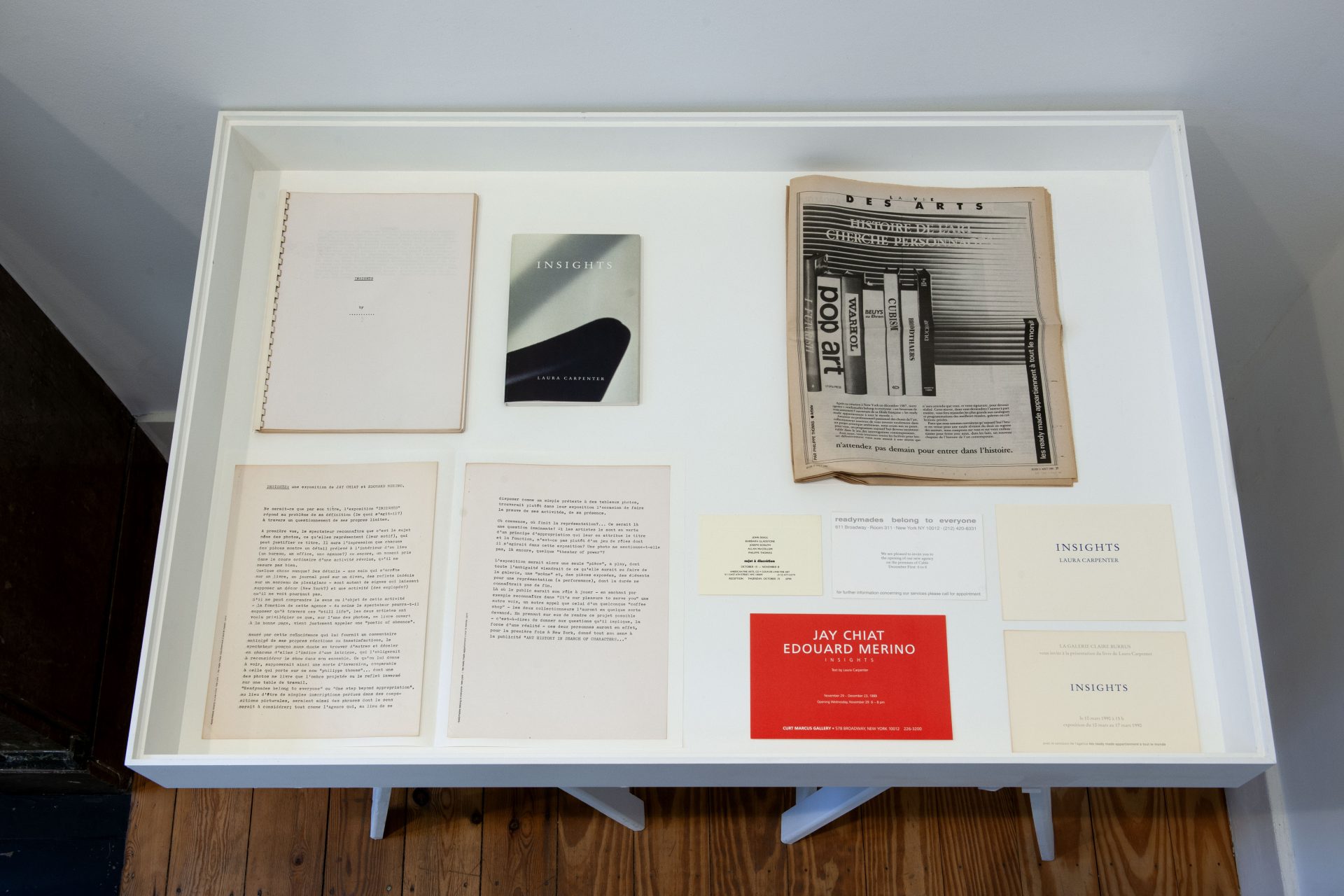

Insights, installation views at Jan Mot, 2021 (from left to right, from top to bottom: Edouard Merino, Insight, 1989, cibachrome print mounted on aluminum, title card with text: "EDOUARD MERINO Insight 1989", photograph: 120 x 180 cm, title card: 4,5 x 11 cm, edition 1/3 and 1 A.P.; Edouard Merino, Insight, 1989, colour photograph and title card with text: "EDOUARD MERINO Insight 1989", photograph: 165 x 247 cm, title card: 4,5 x 11 cm, edition 1/3 and 1 A.P.; Edouard Merino, Insight, 1989, colour photograph and title card with text: "EDOUARD MERINO Insight 1989", photograph: 120 x 180 cm, title card: 4,5 cm x 11 cm, edition 1/3 and 1 A.P.; Edouard Merino, Insight, 1989, triptych, colour photographs and title card with text: "EDOUARD MERINO Insight 1989", photograph: 60 x 90 cm (each), title card: 4,5 x 11 cm, edition 1/3 and 1 A.P.)

"The Many Aliases of Philippe Thomas", by Emile Rubino, 06/01/22, Frieze

As with all of Philippe Thomas’s work, the exhibition currently on view at Jan Mot is attributed to one of the French artist’s many alter-egos – Edouard Merino. The three large-scale photographic tableaux and the smaller triptych that make up this concise presentation are a part of Thomas’s ‘Insights’ series (all works 1989), which includes six additional photographs (not on view here) attributed to Jay Chiat, another alias. These still lifes provide quasi-forensic ‘insights’ into Thomas’s 1987 installation at New York’s Cable Gallery, where he launched ‘readymades belong to everyone®’ – the agency he operated under until he died of AIDS-related complications in 1995. The seemingly simple service offered by the agency enabled collectors to permanently affix their name to the pieces they acquired. This protocol is best described by Claire Fontaine in her 2012 essay ‘G.C.A.’ as a genuine way to ‘re-enchant the everyday prostitution of commerce’. In signing the work, clients like Merino would thereby take on the authorial function of the artist and partake in art history as Fernando Pessoa-like heteronyms within Thomas’s discursive apparatus.

Central to the exhibition at Jan Mot is the photograph of a folded newspaper on a stiff couch, which discloses the beginning of an article describing how Cable Gallery was ‘transformed into a simulation of an office’. An installation view of the office in question accompanies the article, presenting the viewer with a mise en abyme of ‘the stage’ where Thomas made the pictures. On the opposite wall, an abstract composition focuses on the smooth metallic rim of an ashtray that can also be spotted on the newspaper image. From one picture to the next, Thomas’s approach to photography mirrors the logic of his meta-fiction. As in the photograph of his own name – which appears in reverse lettering and as a projected shadow – everything is doubled and folded onto itself. This moody and monochromatic image also reads like a pastiche of modernist experimental photography, such as László Moholy-Nagy’s 1925 photogram of his hands with the inscription ‘I Moholy’ in reversed stencil letters. In this light, Thomas’s work demonstrates a twofold attempt to project authorship outward so it can be probed and, as in Michel Foucault’s terminology from his 1969 lecture ‘What Is an Author?’, turned into a function.

In her essay ‘Philippe Thomas’ Name’ (2018), Elisabeth Lebovici insists on the vulnerability of the Foucauldian ‘author-function’, which strips the author of their creative role. She identifies the inherent precariousness that comes with ‘undoing the legal and affective protection of the “I”’ as something ‘duly exercised by queer lines of thinking’. Similarly, Thomas’s ventriloquist strategy disrupts the assumed autonomy of the tableau by introducing theatricality through the fictional context in which his pictures exist. With great formal command, he twists the photoconceptualist narrative around the photographic tableau – a form that emerged as a reaction to the prevailing deskilled uses of photography of the 1960s. His slick Cibachromes bring the tableau closer to life by positioning it not only in front of people as an object for passive absorption, but also in between them – within the interdependent network of the art world.

Paired with plexiglass labels attributing the works to Merino, Thomas’s ‘Insights’ offer themselves as tangible proof of his fictional narrative. Yet, there is also an unforeseen intimacy to be found in these large-scale photographs. Provided with clues to the plot, the viewer actively engages with the pictures and the corporate surfaces they depict. As beholders, we act on these photographs as much as they act upon us, so that, beyond the death of the author, they continue to perform the play devised by Thomas and his cast of characters."

Full article

Insights, installation view at Jan Mot, 2021 (Edouard Merino, Insight, 1989, colour photograph and title card with text: “EDOUARD MERINO Insight 1989”, photograph: 165 x 247 cm, title card: 4,5 x 11 cm, edition 1/3 and 1 A.P.)

INSIGHTS: an exhibition by JAY CHIAT and EDOUARD MERINO.

If only by its title, the exhibition “INSIGHTS” provides an answer to the problem posed by its definition (What is it about?) by questioning its own boundaries.

After a quick glance, the viewer will realize that it is the very subject matter of these photographs, and what they depict (their motif), that can justify this title. He will feel as though each and every piece is showing a detail sampled from a location (a desk, an office, an agency?), or again, an instant captured in the ordinary flow of a now completed task whose nature he cannot fully grasp.

Something is missing! Details — a hand that halts over a book, a newspaper left on a sofa, wavering reflections on a piece of plexiglass — are as many indications suggesting a decor (New York?) and an occupation (employees?), which the viewer, however, cannot see.

If he is not able to make out the meaning or the nature of the activity at hand — or the function of the agency — he will at least be able to assume that through these “still lifes,” the two artists aimed to put forth that which, in one of the photographs of a book opened on the right page, is accurately called a “poetics of absence”.

Amused by this coincidence, which provides him with an anticipated commentary on his own reactions or dissatisfactions, the viewer will most likely find other similar instances and decipher a clue to the plot within each of the photographs, which would compel him to reconsider the exhibition as a whole. Thus, what he is given to see supposes a kind of inversion, akin to that of the name “philippe thomas”… which one of the photographs delivers only as a projected shadow or an inverted reflection on a work table.

“Readymades belong to everyone” or “ One step beyond appropriation," instead of existing as mere inscriptions lost within pictorial compositions, would therefore be phrases whose meaning would have to be considered; just as the agency which, instead of setting itself up as an excuse for photographic tableaux, would find their display to be an occasion to demonstrate its activities, and establish its presence.

Where does representation begin, and where does it end ?… This would be a pressing question! If artists are so by virtue of the principle of appropriation, which confers them with the title and its function, in this exhibition, isn’t it in fact more of a role play? Again, does one of the photographs not mention something like a “theatre of power”?

Hence, the exhibition would be a singular piece, “a play,” (une pièce) with all the ambiguity arising from its ability to make the gallery a “stage,” (une scène) and the exhibited works, elements of a performance (une representation) whose duration knows no end.

Where the public would have a role to play — by having the capacity, for instance, to recognize “It’s our pleasure to serve you” as another voice, a different kind of announcement than that of a banal coffeeshop — the two collectors would, to some extent, have gotten ahead of the spectators. By taking on the responsibility of making this project possible — that is to say: to give the tangible strength of a reality to the questions the project implies — these two persons will, for the first time in New York, have made complete sense of the advertisement “ART HISTORY IN SEARCH OF CHARACTERS…”

This text by readymades belong to everyone was written for Insights by Jay Chiat and Edouard Merino, a group of works first shown at Curt Marcus Gallery in New York in 1989. It is the first time that the text is published in English. Translated from French by Emile Rubino.

Edouard Merino, Insights, 2021, installation view, Jan Mot, 2021 (Special thanks to Claire Burrus for making the documents available for the exhibition.)